At a time when there’s a lot of talk about the place of women in jazz (see, for example, the collective work “A l’invisible nulle n’est tenue” (Trad: No one is bound to the invisible) reviewed on couleursjazz.fr a few months ago by my excellent colleague Alain Tomas), I’d like to take a slightly different view and say that jazz has recently become much more feminized in terms of the approach adopted by many young musicians.

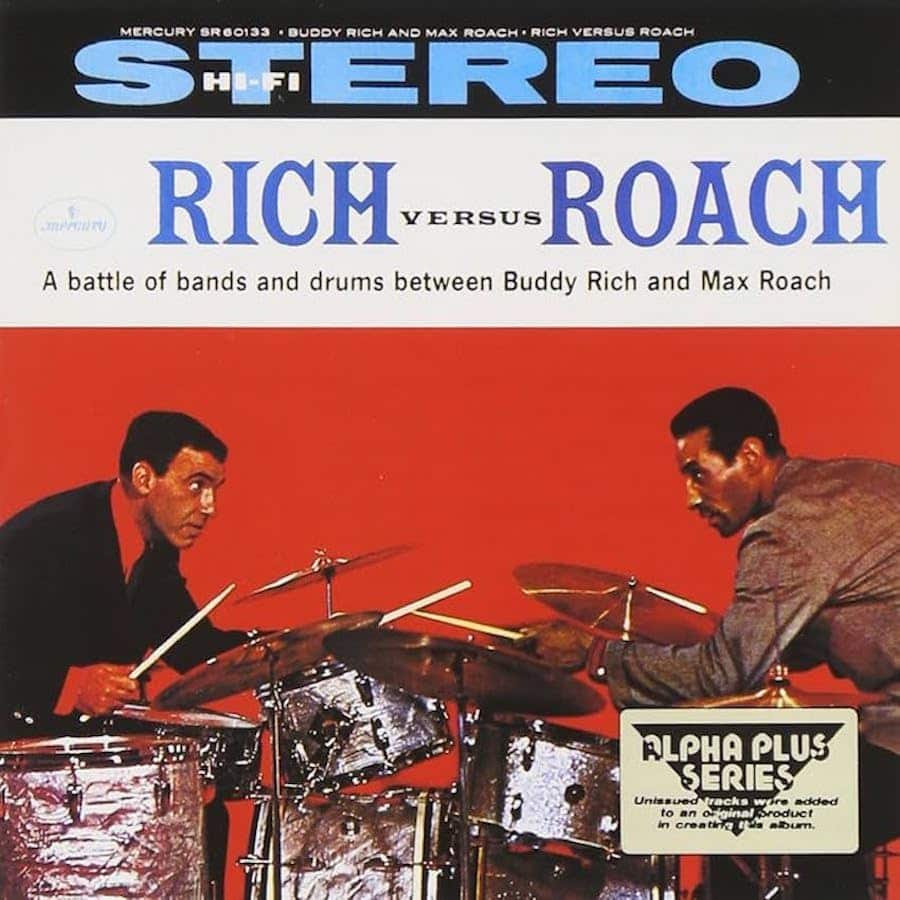

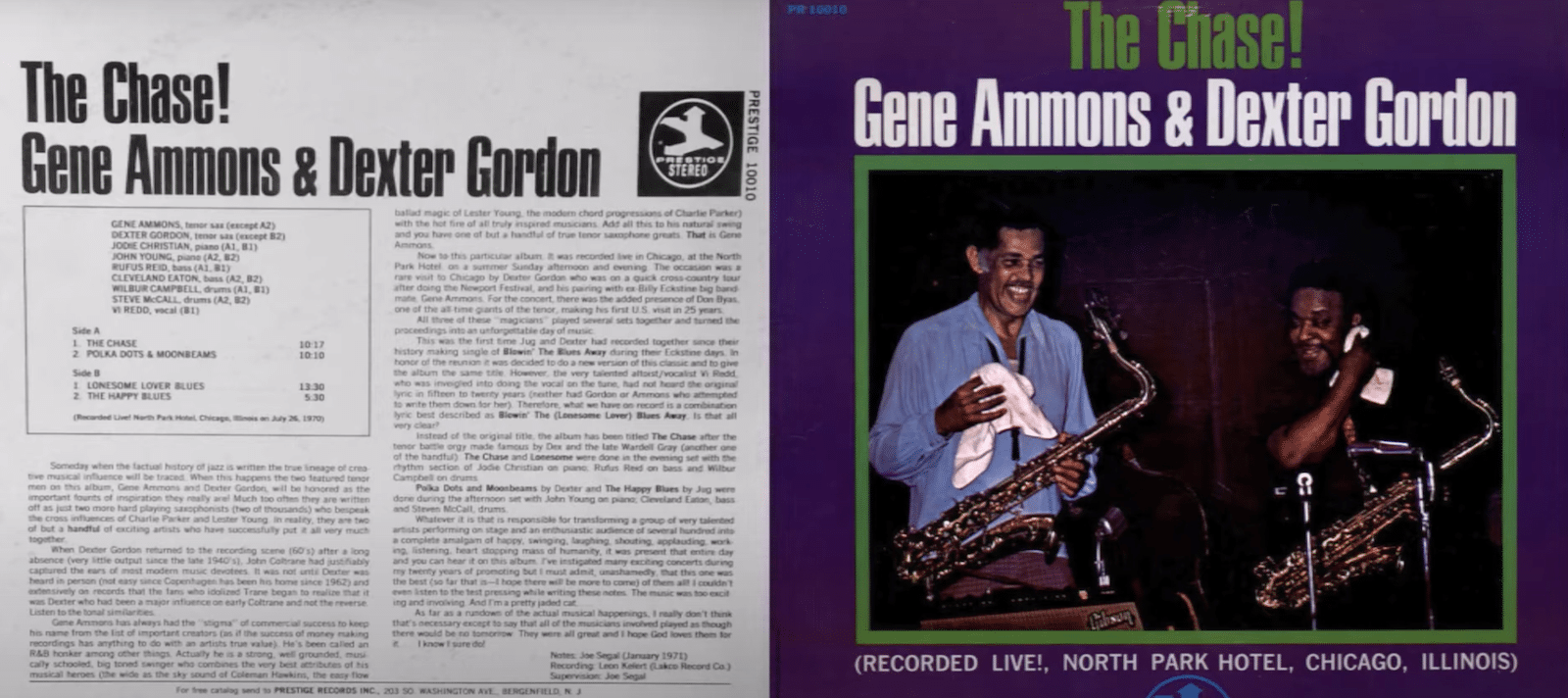

Jazz was originally a “warrior” music. Proof of this is the existence of “battles” in the 40s and 50s. Orchestra battles (Duke Ellington versus Count Basie) of drums (Max Roach versus Buddy Rich) of tenor saxophones (Dexter Gordon versus Gene Ammons)… Even if these battles sometimes resulted in victories, such as that of Lester Young in a historic jam session that pitted him — among others — against Coleman Hawkins in Kansas City, they didn’t prevent each of the belligerents from retaining their value and their fan base, and the “vanquished” could easily continue to deploy their aesthetic on stage and on record. The confrontation was just one episode in a journey in which everyone retained their individuality.

The trend towards less pugnacity and conflict in jazz music can certainly be linked to an evolution in society: armed conflicts have steadily diminished in the West since the end of the last world war, and the presence of soldiers in the population has been considerably reduced. Take, for example, the fact that, at the beginning of the last century, comedy troupers — which have now totally disappeared — were an almost compulsory part of every music hall show.

We can only welcome the fact that war is no longer part of the Western European landscape. But the figure of the “warrior” had a double face: offensive and defensive, and from the medieval knight defending the widow and the orphan to the poilu of WW14, the soldier could be cloaked in obvious prestige.

In the USA, jazz was originally essentially black, and had to struggle to assert itself in a predominantly white and potentially hostile world.

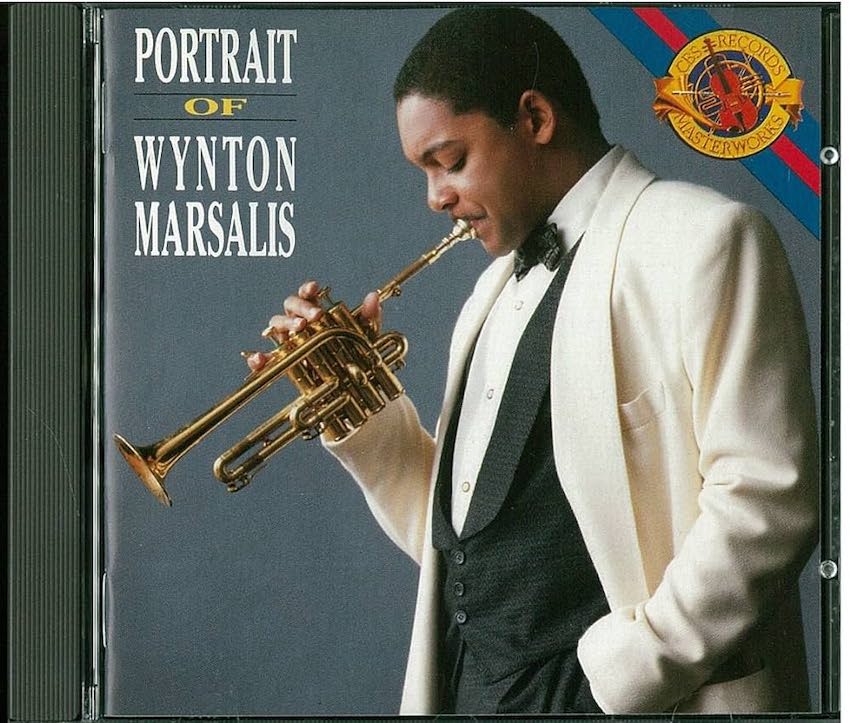

This black struggle in a white world resurfaced momentarily in the ’80s under the impetus of Wynton Marsalis. His desire to have totally or predominantly African-American bands and to claim a filiation with the historic figures of black jazz can be explained by a desire to position himself in the face of a predominantly white American jazzosphere where the most influential figureheads were Michael Brecker, Pat Metheny or Keith Jarrett, among others.

Until the 1960s, with the civil rights struggle, the Black Panthers and free jazz, this offensive approach remained very much alive in American jazz.

Until the 1960s, with the civil rights struggle, the Black Panthers and free jazz, this offensive approach remained very much alive in American jazz.

In Europe, jazz also had to fight against the ostracism of the Nazi occupation.

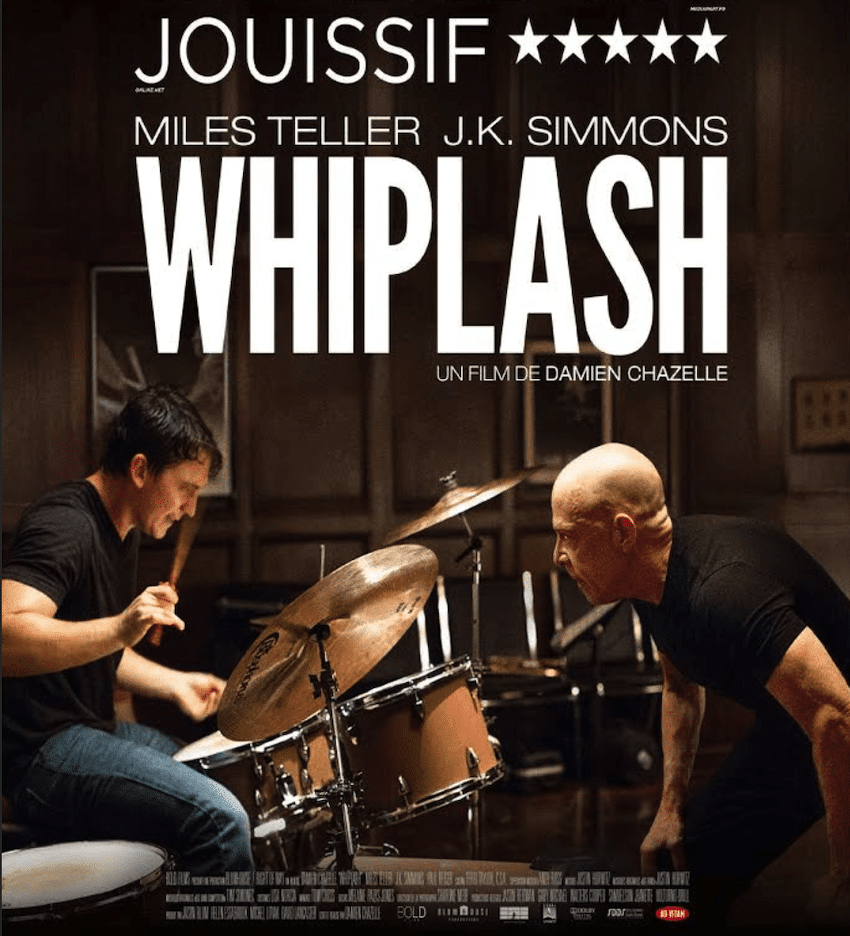

The end of this conflictual atmosphere was, in my opinion, accompanied by a feminization of jazz. One element of this evolution is linked to the fact that the majority of young jazz musicians come from the bourgeoisie, a portion of society that doesn’t have to defend itself in terms of class struggle. Another is the proliferation of jazz schools, in which pedagogues are primarily responsible for transmitting knowledge in a benevolent environment, rather than elders with whom young musicians are confronted in a potentially aggressive dynamic. The film “Whiplash” (highly criticizable in other respects) gives a caricatured image of this.

These young musicians, rarely confronted with conflict, have naturally developed a softer approach to musical practice than their elders.

We can see this in the tenor saxophone, for example, with the virtual disappearance of what used to be known as “hairy” saxophonists, with their big sound and voluntarily tonic phrasing. Today, it’s a fluid-sounding saxophonist like Mark Turner who is often taken as a model by young tenor proponents.

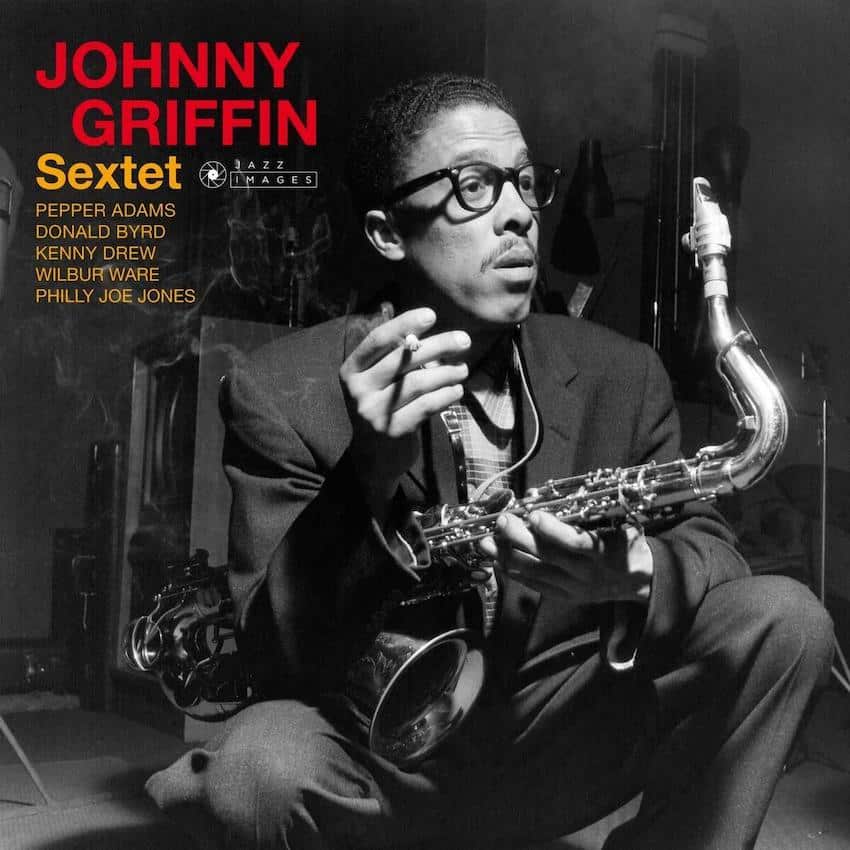

Some thirty years ago, I attended a concert where two saxophonists alternated and then played together, accompanied by the same rhythm section led by pianist Hervé Sellin. Johnny Griffin, the elder, played a first set followed by Eric Barret, then the two played together and Griffin – who had remained subdued during his set – asserted his superiority and in a way “smashed the face” of his younger son, who clearly didn’t have the physical means to resist Griffin‘s offensive. Apart from the generational difference, it was clear that Griffin had a long history of confrontation with his peers, something Barret clearly lacked.

One of the areas in which this “feminization” of jazz is most evident is in the drums. Drums are first about the earth: the toms, originally covered with animal skins, and the snare drum, an instrument of “warrior” origin (see the Napoleonic drum tradition).

One of the areas in which this “feminization” of jazz is most evident is in the drums. Drums are first about the earth: the toms, originally covered with animal skins, and the snare drum, an instrument of “warrior” origin (see the Napoleonic drum tradition).

If you listen to records or watch videos where an old-school drummer (right up to hard bop) takes a solo, you’ll notice that he or she uses toms above all, and only occasionally cymbals. Yet young drummers – frequently influenced by Paul Motian, for example – tend to favor cymbals in an “airy” style of playing, forgetting that Motian, until quite recently, was not a cymbal specialist.

Which young drummer today knows and is inspired by Sid Catlett, Cosy Cole, Jo Jones or even Art Blakey or Max Roach?

Another factor in this feminization seems to me to be the fact that the piano has become the king instrument of jazz. The majority of jazz bands are led by pianists, and the piano/bass/drums trio is clearly the most fashionable formation. Not that the piano is a specifically feminine instrument, but the majority of female jazz musicians are either singers or pianists. So, there is definitely a piano tropism among women. Moreover, in terms of piano playing, the dominant influence – which can be traced back to Bill Evans and musicians who followed in his footsteps – is an approach to the instrument focused on harmony, forgetting that the piano is also a percussion instrument. Which young musician today claims to be influenced by Cecil Taylor or Don Pullen? Who even knows who Lennie Tristano or Eddie Costa were?

Another factor in this feminization seems to me to be the fact that the piano has become the king instrument of jazz. The majority of jazz bands are led by pianists, and the piano/bass/drums trio is clearly the most fashionable formation. Not that the piano is a specifically feminine instrument, but the majority of female jazz musicians are either singers or pianists. So, there is definitely a piano tropism among women. Moreover, in terms of piano playing, the dominant influence – which can be traced back to Bill Evans and musicians who followed in his footsteps – is an approach to the instrument focused on harmony, forgetting that the piano is also a percussion instrument. Which young musician today claims to be influenced by Cecil Taylor or Don Pullen? Who even knows who Lennie Tristano or Eddie Costa were?

A final factor in this evolution is the increasingly frequent presence of female musicians in orchestras composed mainly of young people of the same generation. If we take the example of orchestras led by women such as Maria Schneider, it’s clear that her approach to composition and conducting can be described as feminine, even if her orchestra is predominantly male. This is less true of her elder Carla Bley, who worked as an arranger in a “combat” orchestra such as Charlie Haden‘s Liberation Music Orchestra.

In the past, women have been able to play in predominantly male bands without feminizing them. This was the case of Ella Fitzgerald when she took over the direction of Chick Webb‘s big band after the death of the drummer-leader, and of Melba Liston when she served as arranger in Randy Weston‘s orchestra.

In the past, women have been able to play in predominantly male bands without feminizing them. This was the case of Ella Fitzgerald when she took over the direction of Chick Webb‘s big band after the death of the drummer-leader, and of Melba Liston when she served as arranger in Randy Weston‘s orchestra.

The 50s and 60s also saw the emergence of vocalist duos in which women and men maintained their sexual identity on equal terms: Ella Fitzgerald/Louis Armstrong, Betty Carter/Ray Charles, and I can’t resist the pleasure of recommending the Dinah Washington/Brook Benton duo who, on the track “A Rockin’ Good Way”, indulge in a thrilling and hilarious exercise in mutual flirtation.

There’s no question here of deploring the feminization or gentrification of jazz, but we can deplore the fact that the “offensive” approach has all but disappeared and is no longer part of a musical landscape that has, as a result, lost its diversity.

There’s no question here of deploring the feminization or gentrification of jazz, but we can deplore the fact that the “offensive” approach has all but disappeared and is no longer part of a musical landscape that has, as a result, lost its diversity.

RECENT COMMENTS