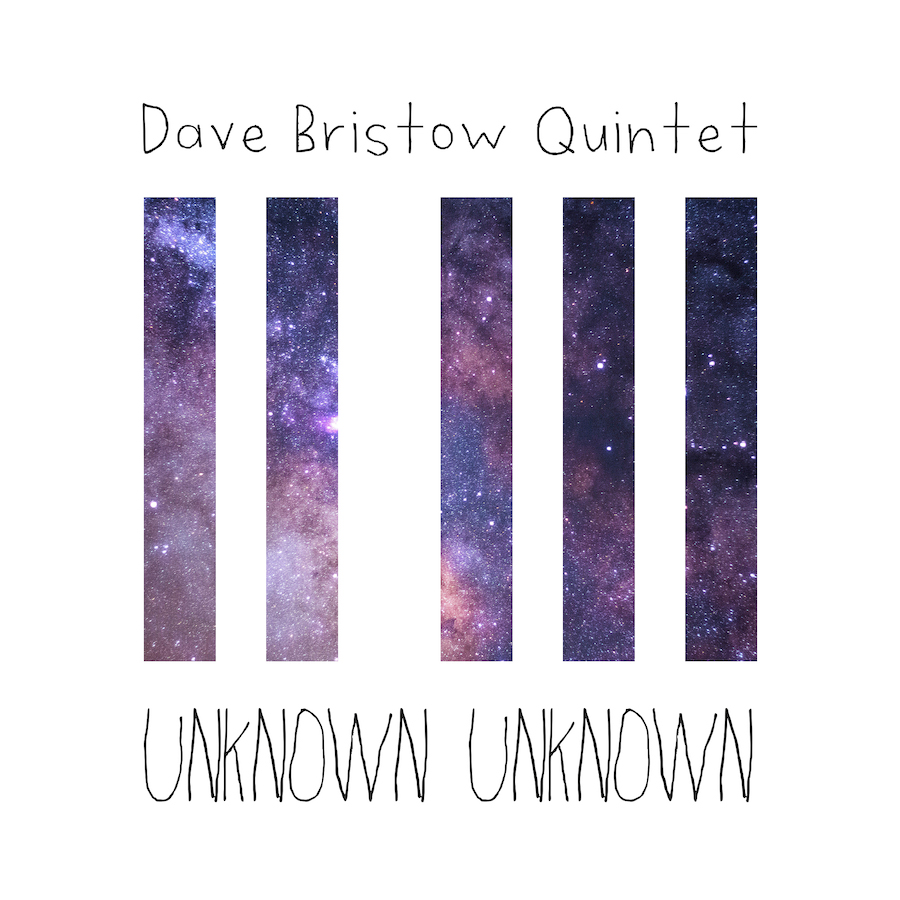

Joining us here today is English pianist Dave Bristow, who has just released his first album with a brilliant quintet under the JMS label entitled ‘Unknown Unknown’. He’s an astonishing artist, full of ideas and one of the brightest talents to emerge out of the UK for quite some time.

In the following interview, we discover the many interesting things he has to say and the personality that informs his music making.

Couleurs Jazz : Hello Dave, you’ve recently released your debut album at the end of a particularly difficult period of the COVID pandemic, an album I think, with a rather strange name:‘Unknown Unknown’

It’s a peculiar name for an album. The word ‘Unknown’ repeated twice.

Can you explain to us the reason for choosing this title?

Presumably, the unknown symbolizes the infinite and much wider realm beyond that of graspable knowledge?

Dave Bristow: It’s a phrase I found in a little book by Mark Forsyth, in an essay in which he tries to explain the joy of finding something fresh at each new visit to the book store by using this phrase. You enter intending to buy something specific and leave with something completely different – something that before entering, you didn’t know existed. So the joy of discovering something unknown. I found it interesting because it’s a bit like that every time you improvise. You’re ready to play something and then something different happens. It’s exactly like that in the world of jazz and improvisation. So it’s important for me to experiment in that respect. It’s also the feeling I harboured towards creating an album for the first time. It was my first experience in a recording studio so I had no preconceptions about what the experience would be like. Hence the title, which may sound a bit strange.

CJ : Can you tell us about yourself? You’re an English pianist living in Paris, which is not so common…

DB: Those who follow Couleurs Jazz and the jazz news in general know about you only through this album ‘Unknown, Unknown’. We presented the album in the Couleurs Jazz Week and it continues to circulate on Couleurs Jazz Radio.

CJ: But we’d like to find out a little more about you, Dave Bristow. Tell us a little bit about your journey, what brought you to Paris for instance?

DB: I’m actually in Paris because I followed my girlfriend here. So I followed for love. I had no previous experience …

CJ: …. no experience with women?

DB: Haha sure! I meant no previous experience of living in Paris, in France or abroad in general. We had met initially in England. She returned to France two months afterwards and I decided to follow her to Paris in September 2018. I didn’t know what to expect!

Fortunately in Paris I met a lot of musicians who helped me to improve my skills in jazz and of course in French!

CJ: Covid followed a couple of years later…

DB: Yes that was a fairly difficult period. As a jazz musician it is very important to play with others – their influences inform your improvising and help you continually improve. But with COVID it all just stopped. I suddenly just stopped playing with musicians because I was trapped at home.

On the flip side, I found myself with a lot of free time which I decided to use to build a project. At the end of that period, I had an album’s worth of compositions ready to be rehearsed and eventually recorded.

CJ: Let’s go back to the album then. We could argue that you’ve limited the risks associated with creating an album by assembling such a strong team of musicians to work with you: Olga Amelchenko on sax, Christian Altehülshorst on trumpet, Gabriel Pierre on double bass, Guillaume Prévost on drums. And some guests : Caloé on vocals, Simon Moullier on vibraphone and Gustave Reichert on guitar…

DB: Yes, in fact I met all the musicians, except one, in a jazz club in Paris, Le Baiser Salé. I met almost all of them at jam sessions at that club. Guillaume (Prévost), our drummer, lives in Toulouse, but he often comes to Paris for jams. I remember a particular jam one morning around 7am with Gabriel (Pierre) and Guillaume where we played Cherokee. It was crazy. I told myself that I had to play more often with both of them. It was also the case with Christian (Altehülshorst) or Olga (Amelchenko). They’re both amazing. I saw them at various points infrequently at that club across 2019. Christian is maybe the first one I played with. He has a very strange taste in clothes. Sweaters with peculiar animals on them… Needless to say, he’s a pretty adventurous musician and has a great sense of humour.

I’d checked out Gustave and Caloé at their gigs in Paris and they’re absolutely wonderful musicians. Simon was recommended to me by Gabriel and he played astonishingly well on the album too!

Of course, when I arrived in Paris I went to all the jam sessions I could; the Caveau des Oubliettes, the 38 Riv, the Sunset, the Duc des Lombards, the Caveau de la Huchette, Le Nouveau Cosmos…

I still visit these clubs regularly to listen to and to play with others – there are so many excellent jazz artists in France and in Paris in particular. I am always learning…

CJ: All the compositions on the album (12 tracks) are yours? Can you tell us a little more about this?

DB: Yes, all the compositions are mine. Some of them I finished writing several years ago. The oldest one is Aurora Borealis which I wrote in 2011, while I was studying in Leeds. I also wrote “Opening Theme” (which opens the album), “Nietzsche’s beard” and “Sunbeams” in 2011. The most recent one is “Labyrinth” which is a contrafact based on George Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm. It’s also heavily influenced by Frank Zappa and has a rather strange melody. It’s less melodic than the other tracks. There’s hints of John Coltrane’s 1960’s sound in the melody too. It’s a mixture of these different influences. I’m influenced by many composers. Olga and Christian have repeatedly told me it is the most complicated piece to play and that I should stop writing songs like this. There are a lot of wide intervals in the melody that are not easy to play or sing.

Despite this, my goal in general is to create melodies that you can easily sing and remember. Exceptionally on this track I wanted to deviate from that.

I also wanted to create a different sound world for each track.

CJ: You stress a lot of importance on melody. All the tracks have very beautiful melodies – the arrangements seem to come afterwards but they still manage to enhance the songs. Also, the contributions of the fine soloists on the record bring very personal touches to each of the songs. The themes are quite optimistic, you get a sense of boundless enthusiasm, though some tracks are more a bit more contemplative like “Refractions”…

DB: Yes, some of themes are quite optimistic but not all – I wanted a variety of thematic material in order to express the diversity of the human condition – some are a little more tragic, like ‘UB-14’ or boisterous like ‘Human Is’

CJ: UB-14 is a very poignant theme?

DB: Yes, in fact the direct translation of the title ‘UB-14’ is Ubiquity Brave 14. There’s a story about a prison camp in Russia behind the title. It’s inspired by an essay by an activist called Nadejda Tolokonnikova, who belongs to the group Pussy Riot – she was sent to a camp by Putin for 3 years for protesting against his regime. PC-14 was the name of the prison block in the camp in which she and several other women were detained. Many women there died because of the abuse they suffered at the hands of the corrupt prison wardens and because of grueling manual labour.

Despite all of this, there was still an air of hope among this brave community of women. I was touched when I read this. So I decided to write this song about the experiences of these women – that captures the bravery and hope they shared and the tragedies they suffered.

CJ: Olga Amelchenko must have been touched by this story too!

DB: Yes, I empathize that she is going through a difficult time at the moment because of the current events in Russia. This composition predates the latest events. But it’s sadly and unfortunately still relevant.

For all the ‘enthusiastic’ music I write, I’m also heavily influenced by composers of the romantic era like Felix Mendelssohn, Frédéric Chopin and Sergei Rachmaninov – all of whom have written music which could be described as being on the more tragic side of the emotional spectrum.

The accompaniment for my song ‘Réflexions’ is based on a Chopin etude (Opus 25 #1), an Etude of arpeggios in Ab major. The figurations in the piano part of ‘Réflexikns’ are in Eb major and slightly different but the study of that particular Chopin Etude several years ago must have informed the writing process of my song.

CJ: There is also a guest singer, on that song Caloé?

DB: Yes, she sang beautifully! It’s the only song in French. I really like the idea of compositions that can be sung. The lyrics are by Caloé which gives more of her personal touch to the track (Réflexions). There are several high points of emotional intensity in the song, and others with a lot of restraint. She and the group were able to carve out that emotional arc wonderfully!

CJ: What do you think of jazz today? Why did you choose such a difficult path?

DB: I love jazz. I think there’s a lot of hope for its future. There are so many great artists around the world who are carrying on the tradition of a music that is already so rich and colorful. I am very happy to be part of this tradition and to have the opportunity to make a personal contribution to it. Career wise, it’s certainly a difficult way to live sometimes, but I have so much admiration and inspiration for this music. It is a music of freedom. Most importantly it’s an African-American music at its roots and I think it’s very important to respect that.

I think it’s an art form that’s very open to mixing with other styles and genres of music. It is a perfect music for an artist who wants to experiment, to create. In my opinion it is a music without limits. Sometimes you lose listeners because of the ostensible lack of boundaries, but, to me at least, it’s music that is always interesting and always evolving.

CJ: We can only agree with such statements. But what’s interesting is that unlike some artists, you claim to embrace the term ‘jazz’, whereas some of your colleagues seem to be a little ashamed to say they are jazz musicians. Not ashamed, but they almost try to hide and they don’t claim the term jazz… Not to scare the listeners maybe …. What do you think about it?

DB: It’s a great honour and privilege for me to be a jazz musician. I think that whilst jazz can indeed embrace all other musical genres, it is very important for today’s musicians to respect the traditions of the past because it is a very rich music with a history of amazing innovators. Respect of the tradition on the one side and a dedication to creation on the other. That’s the job of today’s jazz musician in my opinion. To find his own personal way.

Of course unique musical creations without prior knowledge of the past can certainly happen. But in my opinion it’s important to know and respect the tradition first.

That said, composition, for me, is about finding things in music that make me uncomfortable and not being afraid to explore these ‘Unknown’ realms. Improvisation is a form of composition in fact, when I’m unsure of myself while I’m

improvising, sometimes I surprise myself.

When you listen to my music there are certainly some very obvious influences. They’re hard to avoid and I’m certainly quite open about sharing who I’m influenced by.

But that’s not the most interesting part of the process for me; exploring the musical ‘roads less travelled’ and challenging myself to try new things is what I’m more interested in.

I have a lot of respect for the listeners, I try to compose themes that inspire them; themes that are memorable and that you can sing, even in the shower! It’s a tough thing to do for a jazz artist because there’s a tendency amongst jazz composers to write melodies that are as complex as the things they want to play when they improvise. I think think this stems from how jazz musicians are educated. We’re taught about all of the available approaches to chord changes, all of the possible ways to reharmonize a standard, all of the ways to make a song more complicated – which is important in it’s own right. But we’re not taught about what to leave out. For writing themes and melodies this is really important. Nobody is going to be able to sing or remember your tunes if there are no pauses for breath. Most of the best melodies I’ve heard are simple. If the melody is strong first, then the song is a much better vehicle for melodic improvisation. I think the best melodies are also independent – they still have a character when you take all the chord changes out.

It was important for me on this album to write music that is accessible to everyone. If my music can help people, to feel good or better by listening to it, then I’ve done my job properly.

When listening to the album Giant Steps, by John Coltrane, the improvising is very complicated, sophisticated and dense, but you can remember all the melodies. Tunes like Naïma, Cousin Mary, Spiral, I could sing them over and over. It’s the same thing with Thelonious Monk… He wrote around 70 songs and I can remember almost all of his melodies. He has a style that is so unique and so awkward to imitate. Those who try for the most part, fail… !

CJ: What are your short and medium term projects?

DB: So recently I’ve written over 200 small compositions, short themes, between 20 and 50 seconds. And I would like to write a book of composition exercises based on those. It would help music students wanting to develop a more advanced harmonic/compositional facility at the piano. I also have six piano preludes that I’ve written (with four more to follow) that I’d like to record. That would be more of a classical project than a jazz one though. I’m also working on a second album for the quintet. I’d be using the same musicians with the possible addition of a singer to communicate my feelings about current events in the world. I would also like to explore a few more electronic timbres on this album as well – I like the idea of improvising only on the acoustic piano and adding Rhodes, electronic organ and synth pads to fill out the sonic atmosphere. I’d like to write more lyrics too.

I would also like to invite a guitar player again for my next project. I often compose on guitar. I’m not a trained guitarist per se, but I have an ear for it and I’m very influenced by guitarists like John Scofield, Pat Metheny and Kurt Rosenwinkel. I’ve transcribed some their music and that’s fuelled the desire to write for the instrument. Of course I’m a pianist at heart but I have a huge admiration for guitarists in general.

On this first record, I invited the guitarist Gustave Reichert on two tracks (Aurora Borealis and Nietzsche’s Beard) and he played fantastically.

This general interest in the guitar is also a possible gateway into the genres of fusion and rock for me in the future.

In improvisation, the language of guitarists is very different from that of pianists – there’s a very rich repertory in classical piano canon from Bach to Chopin through to Olivier Messiaen and all the other great composers of the 20th century, then with all the great jazz composer-improvisers like Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett, Brad Mehldau…

So I’m influenced by that, but I think there’s a unique language that guitarists have to offer. Sometimes when I’m practicing I transcribe the solos of guitarists from records I like with my right hand and also transcribe the left hand of the bassists playing behind those guitarists at the same time – this is fairly standard practice for jazz organists.

I learn a lot from transcribing these guitarists (as well as many other piano players and horn players). It’s a way forward for me. It symbolizes to me that there isn’t ever an end point in Jazz, just lots of starting points. There’s always more to learn…

CJ: One last question. Any dreams?

DB: I’d love to work with those three great guitarists I mentioned earlier. I would also like to discuss music with Herbie Hancock. He along with Oscar Peterson were my first real influences in jazz at the piano. I owe Herbie a great deal. I can’t describe the magnitude of influence he had on me. With each of his albums I learned something: how to approach swing, how to compose, how to interact with other musicians, rhythmic energy in jazz, interesting harmonies and how to play over changes.

He, Bill Evans and Keith Jarrett were huge for me.

More recently the music of the late Barry Harris has had a huge influence on me. Over the last few years I noticed that something was missing in my improvising. I discovered eventually that it was a lack of real traditional bebop in my playing – and Barry’s music helped me to fill in the gaps there. When I started playing jazz at 18, I was actually actively avoiding Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, it sounded too old fashioned to me. It was only much much later when I really started to get into that music and to realize how mistaken I was.

When I arrived in France, I realized the importance of these composers too because everyone was improvising fluently over their tunes.

Bebop is always my starting point for practicing these days because it allows me to experiment even more on the bandstand when I perform. Emulating the bebop players helps me develop my technique at the instrument, sometimes more so than by emulating the more modern players. I play a lot of Bach and Chopin too.

This mix of influences may sound a bit strange. But it’s a huge job to mix the past with the modern, to create something new. That’s the responsibility of an artist in the 21st century.

Ultimately it’s a lifestyle I’m happy with. Especially in Paris. I’m very happy to be here. In England, when I was living in London, I was surrounded by incredible musicians too. But distance was always a problem there – London is very large – nearly equivalent in size to all of Île de France. In Paris, everything is much more accessible – you can find so many different kinds of jazz in the city every night and I’m very grateful for it. I’m having a blast!

Line Up:

Dave Bristow, piano, compostions

Christian Altehülshorst, trumpet

Guillaume Prévost, drums

Olga Amelchenko, saxophone

Gabriel Pierre, Double Bass

Guests:

Simon Moullier, vibraphone

Caloé, vocals

Gustave Reichert, guitar

“Unknow, Unknown” is un album JMS label

Photos: Gaby Sanchez pour Couleurs Jazz.

RECENT COMMENTS