First evening

I’ve barely arrived in Noyon – where I’ve come to review the Jazz Festival – and already I can feel myself falling in love with this little Oise town. Was? No, you can so stupid sometimes!

Is, not was, because there’s nothing old-fashioned or outdated about Jazz in Noyon. After a stroll through the town’s sumptuous ancient monuments (the cathedral is to die for!), I wait for Philippe Laredo, the festival’s president and the musicians at Le Stromboli restaurant, where they’ll be playing this evening.

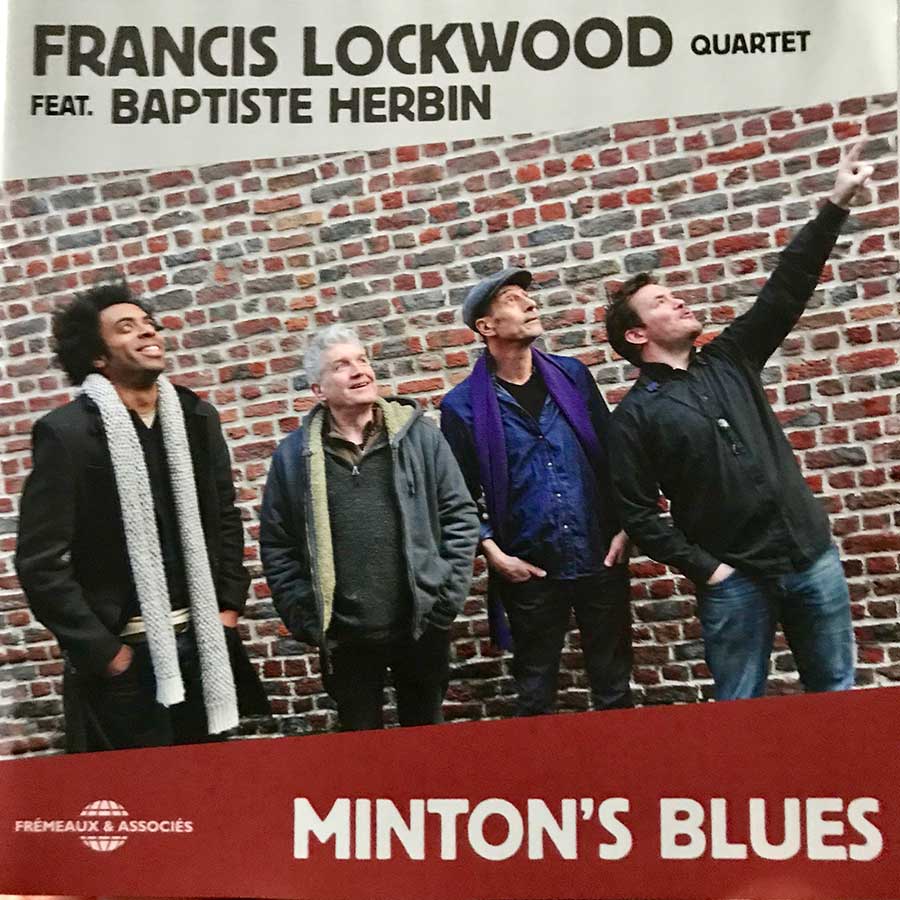

I meet up with Baptiste Herbin – whom I’ve known for a good twenty years – and discover the trio of guitarist Andry Ravaloson, born and raised in Madagascar, whom I’m just discovering.

I was able to follow their sound check at the end of the afternoon before the concert and, as is often the case, it was very interesting and it was immediately clear that Baptiste and the trio knew each other well. After a remarkably fluid guitar solo, the alto sax took flight. Yes, literally takes off, negotiating harmonic-melodic twists and turns with breathtaking virtuosity, as usual, one might add. We already know we’re in for an evening of dense jazz, rich in solos, unison, drive, groove…

Then it’s a slower theme that the guitar exposes in airy arpeggios. It sounds like “Beautiful Love”, but it’s not, and the lyricism of the viola makes you melt with pleasure. Sober and chordal, the guitar accompanies a limpid double bass solo.

The six-string solo that follows clearly demonstrates Andry‘s personal harmonic science and phrasing. Herbin‘s solo is magnificent, and for the next piece he switches to soprano, on which he has a softly tart, strongly timbred tone. Then the overall sound takes on fullness and power under the blows of telluric and terribly effective drums, played by Tohery Ravaloson, Andry’s nephew.

It’s easy to get carried away by this musical deluge, with Christophe Hache’s deep, swift double bass taking the first solo, followed by the guitar.

If you want to find Andry Ravaloson‘s source of inspiration, you’ll find it in George Benson and Wes Montgomery, with a dash of Pat Martino. We’re right in the heart of historic jazz, which hasn’t aged a bit when played with as much heart as skill.

And Baptiste‘s stop chorus is no exception, with its high-pitched jumps and twirling phrasing that his three companions observe with broad, delighted smiles. The second set begins with a bop-hard bop theme taken at TGV speed and, paradoxically, Baptiste‘s solo begins very gently before gathering momentum and slaloming across the harmonic grid, introducing a few bars of “L’amour est enfant de Bohème“.

This saxophonist will never cease to delight and amaze us with his inexhaustible inspiration and his approach to the sax that is both vintage and perfectly contemporary. The guitar solo that follows, in its own way, embraces the same harmonies, giving space to silence, which, as we all know, is part of the music, under the crackle of a tonic, sharp drum kit – which on this occasion takes a first chtonian, leaping solo – and the roar of the double bass.

The next track, in medium tempo, flows smoothly and quietly, like a peaceful meandering river. The swift double bass introduces the following theme in an absolute solo, with occasional delicate harmonics. Baptiste and Andry each contribute a chorus with a melodic line of total cantabile legibility. And it’s the rhythmic pair who conclude the piece in a duet full of bouncing sap.

Then again, Baptiste launches into an absolute solo in which he moves up and down the melodic line of “You Don’t Know What Love Is“, before the trio joins in with majestic slowness. And the final track is yet another hardbop semi-ballad, showing just how comfortable these four boys are with an idiom that was originally American, but has been appropriated by a number of European musicians and those from Africa – Madagascar, in this case – to make it their own. The formidable young drummer is once again in the spotlight, and his archly melodic toms work wonders on the guitar break, while Baptiste embosses both alto and soprano in a trumpeted, rough vocal of the finest effect.

Second evening

The second evening kicks off with a “boys next door”, the Amiens-based group Anagramme.

Their electric, crossbred music mixes lyricism with the power of jazz rock, without falling into the pitfalls of this sometimes very (too?) dated style. The soprano sax is eminently melodic. The electric guitar’s solos are confidently rocking, and – in the absence of keyboards – provide a relevant harmonic foundation.

The electric bass is sometimes fluid in solo, sometimes earthy in accompaniment, and leans more towards Jaco Pastorius than the instrument’s speedsters. As for the drums, binary most of the time, they provide remarkable support and drive the ensemble beautifully.

The electric bass is sometimes fluid in solo, sometimes earthy in accompaniment, and leans more towards Jaco Pastorius than the instrument’s speedsters. As for the drums, binary most of the time, they provide remarkable support and drive the ensemble beautifully.

As for the compositions, they are generally original and interesting, drawing their inspiration from Albania or elsewhere. It’s always interesting to cross paths with groups from the “provincial” terroir who have a clearly national dimension.

It’s a fact that France is a fertile breeding ground for jazz styles as diverse and upmarket as those to be found abroad, the USA included. It’s a pity that this concert attracted only a sparse – but enthusiastic – audience. It’s true that it’s a weekday and the people of Noyonnais and the surrounding area may have to work early tomorrow morning.

So it’s to Philippe Laredo‘s credit that he took the risk of programming two little-known but first-rate bands on a Thursday evening.

The word-of-mouth that will undoubtedly follow these two concerts will undoubtedly bring in larger audiences next year for the weekday concerts.

————-

Mark Prioré‘s trio, which follows, gets off to a strong start with a densely layered theme in which the piano’s repetitive chords and arpeggios rub shoulders with the Elie Martin- Charrière‘s furious drumming, before calming down into a sort of serene hymn in which the double bass of Juan Villlarroel comes into sharper focus.

It’s this same bass that opens the next track with a perky little motif, joined by its two companions with a welcome lightness of touch. A lovely melody emerges from the pianist-leader’s fingers, a timeless melody that smacks of the good old days without being old-fashioned.

It’s this same bass that opens the next track with a perky little motif, joined by its two companions with a welcome lightness of touch. A lovely melody emerges from the pianist-leader’s fingers, a timeless melody that smacks of the good old days without being old-fashioned.

A touch nostalgic perhaps, but in fact this type of jazz is ageless.

A touch nostalgic perhaps, but in fact this type of jazz is ageless.

The next track, inspired by the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, is again repetitive and intense, and it seems that this trio is basing its playing on energy as much as melody, which is rarely the case with an acoustic piano/bass/drums trio. Then it’s back to a serene, gently melodic theme, followed by a new one that expresses joy in a stimulating and… new way.

For me, this high-level trio has the flaw of being too confined to an aesthetic of opposition or systematic succession between vigorous themes and lilting ones. But it’s young and has plenty of time to evolve towards greater diversity.

For me, this high-level trio has the flaw of being too confined to an aesthetic of opposition or systematic succession between vigorous themes and lilting ones. But it’s young and has plenty of time to evolve towards greater diversity.

Third evening

As is often the case, the balance of tonight’s two concerts is fascinating to follow, allowing me to hear live musicians I know little about, such as pianist Françis Lockwood, violinist Johan Renard and Michael Olivera the fabulous drummer in Daniel Garcia‘s trio.

In the evening, Daniel Garcia begins. Softly and alone at first, with a joyful little piano arpeggio that quickly becomes Hispanic when the left hand enriches it with sumptuous chords and the music swells, swells, swells.

Then the bass and drums join in, and the magic begins. Of all the piano trios on the planet, this is clearly one of the best and most original. Its Iberian accents are never caricatured, and the culture of flamenco is as deeply rooted in these musicians as that of jazz.

Then the bass and drums join in, and the magic begins. Of all the piano trios on the planet, this is clearly one of the best and most original. Its Iberian accents are never caricatured, and the culture of flamenco is as deeply rooted in these musicians as that of jazz.

The second theme, in fact, is of flamenco origin, and unfolds in supple melodic volutes over a swaying rhythm, which Olivera handles with impressive finesse and musicality. We’ve rarely heard this kind of beauty in France, where Spanish musicians are a rarity, and when Olivera takes a crackling solo on skins and rim shots, then rolls on toms and cymbals, he unleashes a rousing thunderbolt. This is followed by a beautiful, meditative melody with Ravel/Debussy accents in piano solo, which the double bass of Reinier “El Negron” Elizarde and drums only accompany with refined playing after a few minutes. The bassist then takes a beautiful, serenely serene solo on bow, before the melody expands and ends with a few stinging notes from the piano.

The next track is partly sung: a tender, repetitive melody over which the drummer takes a powerful solo. This is followed by a lively, playful theme, on which the double bass roars, then leaps into the bass over the pearled notes of the piano, which briefly quotes the theme from Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme“.

The next track is partly sung: a tender, repetitive melody over which the drummer takes a powerful solo. This is followed by a lively, playful theme, on which the double bass roars, then leaps into the bass over the pearled notes of the piano, which briefly quotes the theme from Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme“.

The final piece, based on pre-Flamenco rhythms, begins with a small rhythmic motif played jointly by the three musicians, then expands, accompanied by a deep melody sung by the pianist before returning to more melodic gentleness on sharp left-hand chords. And the encore – which was impossible to escape, given the enthusiasm of the overexcited audience – is a pretty musical nursery rhyme that’s impossible to resist, and on which Garcia has the audience humming along, rightfully won over. A ma-gni-fi-cent start to the evening!

The final piece, based on pre-Flamenco rhythms, begins with a small rhythmic motif played jointly by the three musicians, then expands, accompanied by a deep melody sung by the pianist before returning to more melodic gentleness on sharp left-hand chords. And the encore – which was impossible to escape, given the enthusiasm of the overexcited audience – is a pretty musical nursery rhyme that’s impossible to resist, and on which Garcia has the audience humming along, rightfully won over. A ma-gni-fi-cent start to the evening!

———

It’s hard for Francis Lockwood and his two friends to succeed Garcia‘s trio triumph.

But their small, modular line-up is so original that they had no trouble winning over the packed audience at the Centre Culturel.

Piano, violin and sax (alto or soprano), declined in piano-violin duets – on an excellent “Someday my Prince Will Come“, where Johan Renard’s violin ventures into the high range without losing any of its musicality, while its compatriot kneads his 88 keys with delightful vigor – or in a sax-piano-violin trio – on “All the Things You Are“, where the two high-pitched voices (Baptiste on soprano) intermingle beautifully over Lockwood‘s chords and bouncing bass.

Piano, violin and sax (alto or soprano), declined in piano-violin duets – on an excellent “Someday my Prince Will Come“, where Johan Renard’s violin ventures into the high range without losing any of its musicality, while its compatriot kneads his 88 keys with delightful vigor – or in a sax-piano-violin trio – on “All the Things You Are“, where the two high-pitched voices (Baptiste on soprano) intermingle beautifully over Lockwood‘s chords and bouncing bass.

Then there’s “In a Sentimental Mood“, a soprano-piano duet in which the complicity between Francis and Baptiste is obvious, producing little marvels of virtuoso tenderness.

Then there’s “In a Sentimental Mood“, a soprano-piano duet in which the complicity between Francis and Baptiste is obvious, producing little marvels of virtuoso tenderness.

Then a trio with the alto sax, this time on “The Days of Wine and Roses” interpreted in a playful manner by three lads for whom this music holds no secrets.

The violin alternates between guitar-style pizzicato and bowing, while the alto sax races through the instrument’s middle register. This is followed by a solo piano theme in which Lockwood gives free rein to the rhapsodizing vein of a pianist steeped in the jazz tradition he has made his own, and in which he expresses a personality of great generosity. This is followed by Django’s beautiful “Nuages“, but your devoted columnist is getting tired and takes a little nap in the dressing room for 1/4 hour.

And when he returns, semi-comatose and staggering into the concert hall, the three lascars are slaloming gaily on “Libertango“, which is one of the best wake-up calls ever. A standards recital without double bass or drums? That doesn’t exist anywhere. Well,it does: at Jazz in Noyon! And it’s a delight to hear.

And when he returns, semi-comatose and staggering into the concert hall, the three lascars are slaloming gaily on “Libertango“, which is one of the best wake-up calls ever. A standards recital without double bass or drums? That doesn’t exist anywhere. Well,it does: at Jazz in Noyon! And it’s a delight to hear.

Day four

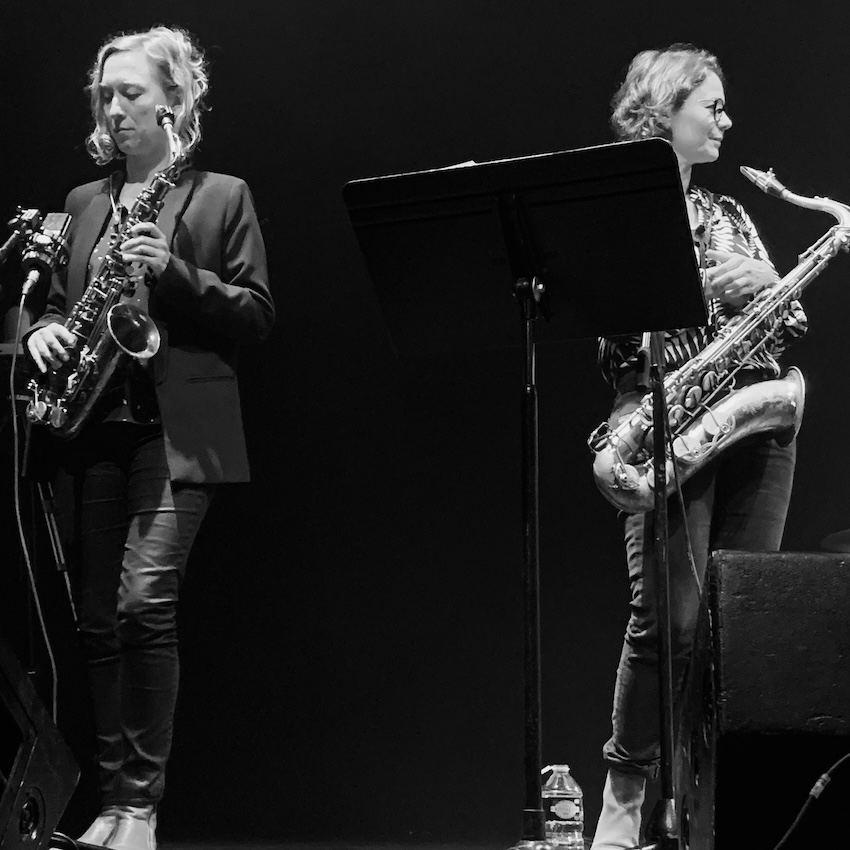

Saturday begins early, just after lunch and in the downtown Théâtre Le Chevalet, with a sax ensemble joined by Baptiste Herbin after they have presented a theme from their repertoire on their own.

This is more the music of a composer like Glazunov than jazz.

But when Baptiste joins in, on Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing if it Ain’t Got that Swing“, they go to another level and start improvising.

But when Baptiste joins in, on Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing if it Ain’t Got that Swing“, they go to another level and start improvising.

On “Spain“, Chick Corea’s hit, the overall sound of the ensemble is velvetily smooth, before toning up on the second half of the piece, on which Baptiste‘s solo soars beautifully.

This is followed by “Misty“, Erroll Garner’s beautiful ballad in which the guest alto soars right from the start of the melody. And the encore is “Spain“, beautifully recrafted with a terrifying solo from Herbin.

———

As for the afternoon’s gospel choir (the Moïse Melende Choir), it was quite impressive: magnificent vocal ensemble, beautiful solo voices, perfect pronunciation of English, accompanied by an excellent keyboard-percussion rhythm, swinging and dancing on stage, and clapping in the audience… And all this can be found in the deep south of the north of our beautiful Hexagon! What do the people want, goddammit?

—–

—–

The evening proper kicks off with the quartet of Médéric Collignon, also a patron of couleursjazzradio.fr.

Médo kicks things off on the cornet, then launches into a breathtaking vocal solo – as usual, one might add – followed by Yvan Robilliard‘s piano.

Franck Vaillant‘s drums, as always, crackle and whirr with polyrhythmic, colorful exuberance, while Emmanuel Harang’s electric bass, all supple, low-key roundness, lends the ensemble unshakeable support.

Franck Vaillant‘s drums, as always, crackle and whirr with polyrhythmic, colorful exuberance, while Emmanuel Harang’s electric bass, all supple, low-key roundness, lends the ensemble unshakeable support.

Médéric has switched to the pocket cornet, then sings magnificently, twirling from low to high register with a phrasing that’s terribly neck-breaking without being ultra-fast. This first-rate, original instrumentalist has a totally unique way of singing, so inventive that it puts him on a par with Bobby Mc Ferrin, Beñat Achiary and Phil Minton.

Médéric has switched to the pocket cornet, then sings magnificently, twirling from low to high register with a phrasing that’s terribly neck-breaking without being ultra-fast. This first-rate, original instrumentalist has a totally unique way of singing, so inventive that it puts him on a par with Bobby Mc Ferrin, Beñat Achiary and Phil Minton.

This concert is an enchantment because, in addition to the solo performances of the quartet members, the group possesses a full band sound, both subtle and punchy, colorful and joyful, which is perfectly suited to the acoustics of the theater and delights the audience. Médo‘s vocal solo of singing, growling, tongue-clicking, guttural belching and body percussion is absolutely unheard-of, and the cornet solo that follows, while Robilliard has switched to electric keyboard, is lyrically beautiful. Switching to funk, the band rips things up, as they say nowadays, but does so with a gentle violence that is totally bluffing.

Collignon is a great leader, a gatherer of sidemen and an outstanding organizer of sounds: a post-modern Duke Ellington with roots deeply irrigated by the language of both acoustic and electric jazz, which he masters in a magnificently unprecedented way. Tonight’s repertoire is supposed to be a tribute to John Scofield. To tell the truth, we don’t really recognize the American guitarist’s aesthetic, but we don’t care, it’s so beautiful!

Collignon is a great leader, a gatherer of sidemen and an outstanding organizer of sounds: a post-modern Duke Ellington with roots deeply irrigated by the language of both acoustic and electric jazz, which he masters in a magnificently unprecedented way. Tonight’s repertoire is supposed to be a tribute to John Scofield. To tell the truth, we don’t really recognize the American guitarist’s aesthetic, but we don’t care, it’s so beautiful!

On the other hand, we’d love Sco to hear this music one day and, although I don’t know him very well personally, I’m convinced he’d be delighted and thrilled and – who knows? – consider hiring those super-talented little Frenchies that burger-eaters don’t usually bother with.

The last track begins with a crazy African drum solo, alternating rolls of toms, crackles of bells and pads, and few cymbals. It’s a real blast, and when the rest of the band joins the valiant Vaillant, the stage is so hot it’s almost like a slope that is anything but snowy.

The last track begins with a crazy African drum solo, alternating rolls of toms, crackles of bells and pads, and few cymbals. It’s a real blast, and when the rest of the band joins the valiant Vaillant, the stage is so hot it’s almost like a slope that is anything but snowy.

A standing ovation, of course, and a thunderous request for an encore, what d’you think!

And it’s a rough, trumpeting cornet that kicks off the theme, before softening for a serene solo that leaves plenty of room for silence, while the electric keyboard grooves its mum, backed by sparing, cleverly binary bass and drums. Médo‘s vocals bring it all to a perfectly limpid close. Truly ma-gis-tral!

——–

Another first at Jazz in Noyon: a guitar-less trio playing the music of Django Reinhardt! Baptiste – him again? This guy is multi-talented, protean and ubiquitous, my word!

Fluid alto sax, pulpy double bass by Sylvain Romano and André “Dédé” Ceccarelli on brushes: an art he masters, even dominates, right next to my man Man the late Ed Thigpen.

The melody of “Night & Day” – arranged by Baptiste and including snatches of Django solos – flows and meanders like a bloody river through a hilly landscape where the colors of autumn delight your eyes, and in this case the hollows of your eardrums. Unlike tenor saxes, not many altists dare to play a trio without a harmonic instrument (piano or guitar).

The melody of “Night & Day” – arranged by Baptiste and including snatches of Django solos – flows and meanders like a bloody river through a hilly landscape where the colors of autumn delight your eyes, and in this case the hollows of your eardrums. Unlike tenor saxes, not many altists dare to play a trio without a harmonic instrument (piano or guitar).

Baptiste, on the other hand, has taken the plunge, revisiting and reappropriating a music that is a priori reputed to be more guitar-based, with formidable skill and extraordinary inspiration. It has to be said that he is backed up by a five-star rhythm section in the Michelin-starred bass/drums duo. And on the two waltzes that follow – including the famous “Indifférence” – with Dédé first on mallets, then again on brushes, he embarks on his soprano from which flows a heady melodic nectar that goes straight to the heart and into the hollows of the “portugaises” (French slang for ears).

The melody of John Lewis’s “Django” is presented with serenity by Sylvain Romano, accompanied by Baptiste‘s discreet alto counterpoint, then taken up by the trio, with Ceccarelli still on the brushes.

It’s magnificent, and this beautiful standard is magnified by an unexpected interpretation that fits it like a glove. Sylvain‘s solo, mainly in the lower registers of the instrument, as all intelligent, sensitive double bassists do.

The following track features a series of exchanges (we call them 4/4s, because each lasts four bars) between Baptiste‘s alto and Dédé‘s drums, where we can appreciate the relevance and precision of the veteran percussionist’s solo playing, both supported by a double bass of unshakeable solidity. After Django’s “Anouman“, Baptiste offers one of his own compositions: a Brazilian choro that imagines the Manouche guitarist in South America’s largest country.

This “Choro Django” is quite simply magnificent, illuminated by a fruity, swift soprano, broomsticks — but how many does Dédé have? (in French “balais” means broomsticks and years of age in slang)

Around 78, it seems, and he uses them to play short solos or a sort of solo accompaniment parallel to Baptiste‘s, while Sylvain watches them, mute with admiration, double bass in hand, before joining in.

What’s amazing and brilliant about Jazz in Noyon is the coexistence of so many different styles of jazz, (Isn’t it Couleurs Jazz signature?) which coexist perfectly and offer the audience a rainbow of different ways of playing this rich, century-old music.

Few festivals allow themselves to do this, and Jazz in Noyon doesn’t go looking for stars of chanson, rap, pop or other peripheral music – who have the right to perform at their own festivals – in order to fill its halls at all costs.

Baptiste starts the next tune with a stop chorus, and it’s waltz time again. Then Dédé (André) takes a masterful solo as an intro to the upbeat “Tea for Two“.

Clearly, if Django had been around longer, he would have adopted the saxophone as his second instrument!

Standing ovation again? Of course, man, what R U thinkin’ about! As they say way down south in the Oise region.

Day five

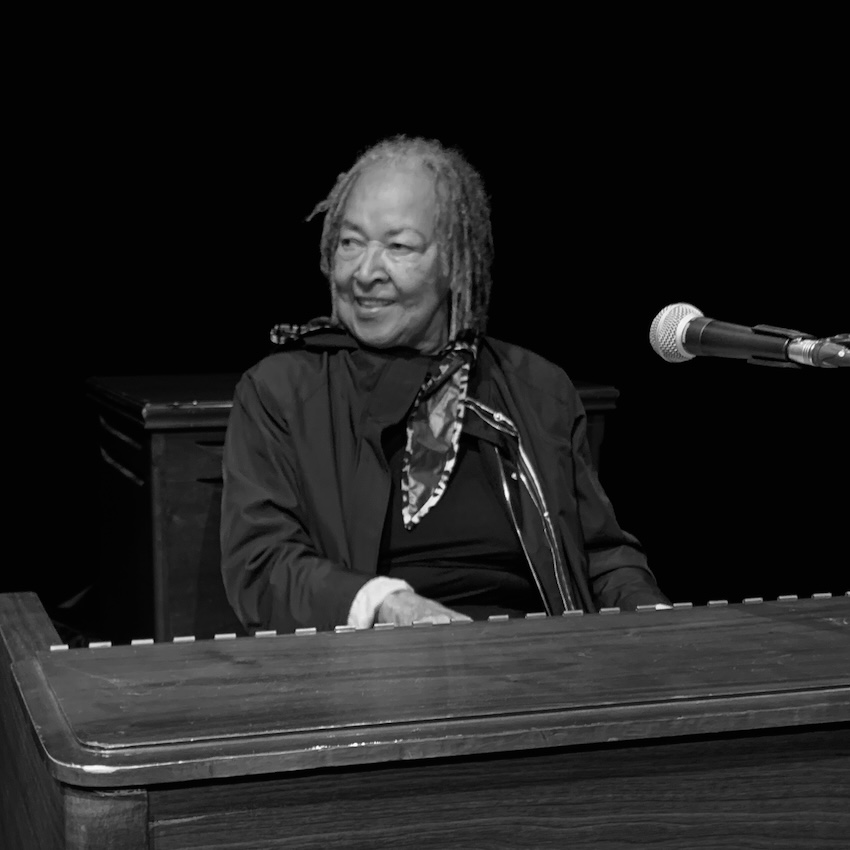

As always, my main Woman Rhoda Scott, sells out.

And on this foggy afternoon, the Théâtre Le Chatelet is again the venue for the final day of Noyon in Jazz. It’s groovy from the word go – and it’s just as well that it’s not groovy at all! Lisa Cat-Berro – who composed the piece – takes the first touchingly lyrical alto solo, followed by the leader, whose pulpy organ pours out its share of fat, swinging tones.

And on this foggy afternoon, the Théâtre Le Chatelet is again the venue for the final day of Noyon in Jazz. It’s groovy from the word go – and it’s just as well that it’s not groovy at all! Lisa Cat-Berro – who composed the piece – takes the first touchingly lyrical alto solo, followed by the leader, whose pulpy organ pours out its share of fat, swinging tones.

The arrangements are very interesting, with an alto that complements the group sound with subtle counter-melodies. For the waltz that follows, Julie Saury unfurls the three-beat rhythm on her drums, and it’s Rhoda who takes the first chorus with a melodic invention of total limpidity and a sound that swells or ebbs like the waves of a barely agitated sea.

The arrangements are very interesting, with an alto that complements the group sound with subtle counter-melodies. For the waltz that follows, Julie Saury unfurls the three-beat rhythm on her drums, and it’s Rhoda who takes the first chorus with a melodic invention of total limpidity and a sound that swells or ebbs like the waves of a barely agitated sea.

On these harmonies, Sophie Alour delivers a beautiful tenor solo, often swift and full of peaceful energy.

The next theme is also by Lisa Cat-Berro, and she again takes the first solo, followed by her more punchy tenor colleague. And it’s Sophie alone who exposes the theme of “Que reste-t’il de nos amours” with a phrasing of magnificent serenity and a tenor tone of great plenitude, while Rhoda behind her slips in hushed chords before taking her turn on a solo just as melodic and tender.

Then comes a composition from Julie Saury (yes, drummers can also compose, in case you didn’t know it, QED) and we sense that we’re in for a drum solo, so much so that Julie pushes her companions with a drive that’s both invigorating and not overdriven.

Then comes a composition from Julie Saury (yes, drummers can also compose, in case you didn’t know it, QED) and we sense that we’re in for a drum solo, so much so that Julie pushes her companions with a drive that’s both invigorating and not overdriven.

In fact, the drummer offers us micro-solos, judiciously placed between the interventions of the other three.

Then it’s Lisa Cat-Berro‘s turn as soloist on a beautiful ballad called… Lisa, where she displays all the splendor of inspired phrasing and a subtly sharp tone. Then it’s the turn of a hit – Bobby Timmons’ Moanin’ – to delight the audience, who clap their hands as the tenor lays out the theme before the organ unleashes its thick, melodious thunderbolt of sound. And who suddenly appears on stage?

My main Man (I’ve got a lot of main Men and I’ll lend them to you whenever you want… if you’re worth it, as they say at L’Oréal when you’re in perfume) Baptiste Herbin, who baptizes the room with his alto sprinkler.

Bring it on, Baptiste! Amen and hallelujah!

And he’ll stay on stage for the next track, an archly funky one introduced by a short solo from Julie Saury, where he delivers a Zeus-esque solo that would have forced the late Dave Sanborn and Maceo Parker – had they heard it – to flee backstage in shame and confusion. The long drum solo that follows is admirably constructed, percussive and melodic, anchored in the soil of the toms and punctually resorting to the cymbals.

Standing ovation and obligatory encore, you bet! And the encore is a hand-clapping Ray Charles hit on which the three saxes go into a sort of delirious chase before the audience is led to sing Oh and Ah.

Standing ovation and obligatory encore, you bet! And the encore is a hand-clapping Ray Charles hit on which the three saxes go into a sort of delirious chase before the audience is led to sing Oh and Ah.

——–

Those that follow are simply a tentet of demonic, frightenking serial killers that – if you don’t know their names – you’re going to want to discover without delay. I list: three keyboards! (You can’t do for less).

Two drums (who says less?). Three blowers, reeds or mouthpieces, plus bass and guitar. No trombone(s)? No, and if you don’t like it, go and buy yourself one! All this improbable instrumental hodgepodge has been matured and concocted by Monsieur Laurent Cugny, composer-arranger and keyboardist emeritus.

And here’s what it sounds like live on ze bloody stage at Jazz in Noyon: it’s the soprano sax (Martin Guerpin) who chorusses first with ductile phrasing over the bottomless background of keyboards (Laurent Cugny, Laurent Coulondre, Laurent De Wilde (replacing the ailing Pierre de Bethmann) drums (Stéphane Huchard, Antoine Paganotti) double bass (Jérôme Regard) and guitar (Manu Codjia).

And here’s what it sounds like live on ze bloody stage at Jazz in Noyon: it’s the soprano sax (Martin Guerpin) who chorusses first with ductile phrasing over the bottomless background of keyboards (Laurent Cugny, Laurent Coulondre, Laurent De Wilde (replacing the ailing Pierre de Bethmann) drums (Stéphane Huchard, Antoine Paganotti) double bass (Jérôme Regard) and guitar (Manu Codjia).

The trumpet (Quentin Ghomari) then takes over, with its crystal-clear timbre. Then it’s the bass clarinet’s turn (Stéphane Guillaume, also on tenor sax), which punctuates its solo with short bursts of silence.

The next track features an electrifying electric guitar solo with a magnificently reptilian sinuosity, and it’s the guitar again that – after the wailing Hammond organ – takes center stage with equal aptness in the theme that follows.

The next track features an electrifying electric guitar solo with a magnificently reptilian sinuosity, and it’s the guitar again that – after the wailing Hammond organ – takes center stage with equal aptness in the theme that follows.

This music is partly based on jazz and pop compositions from the 60s/70s/80s, which it revisits with impressive intelligence, relevance and sensitivity.

This is music made for guitar and electric keyboards, and Laurent Cugny has done well to include two drums and a double bass rather than an electric bass.

As for the blowers, who are clearly jazz-jazz, they bring a freshness and fluidity to the ensemble that is a pleasure to hear. What’s more, all the members of this luxury tentet are, or have been, leaders of their own band(s).

As for the blowers, who are clearly jazz-jazz, they bring a freshness and fluidity to the ensemble that is a pleasure to hear. What’s more, all the members of this luxury tentet are, or have been, leaders of their own band(s).

If they agreed to get together under Laurent Cugny‘s leadership, it’s obviously because they saw an opportunity to take part in an unprecedented adventure that takes music that’s a few decades young and hasn’t aged a bit, and adds a few of the leader’s own compositions.

The next piece, Eddie Harris’ “Freedom Jazz Dance“, requires the blowers to be ultra-precise in setting up the theme, and it’s they who share the solos, offering a magnificent and highly convincing palette of sound colors.

The guitar follows in a hallucinatory, spacey solo, then the two drummers sound their toms and crackle their cymbals before the theme resumes. On the final track (“Carry On” by Crosby, Stills & Nash, totally transformed), the tentet is unleashed and Stéphane Guillaume delivers a killer tenor solo, backed up by companions who all reach the heights of a funk that has absolutely nothing to envy its cousins across the Atlantic.

And for the encore, it’s – guess who?- Baptiste, of course, who completes the trio of blowers on Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo“. It’s in the old pots…, as everyone knows, and this band of young pals leaves plenty of room for their guest, who graces us with a splendid alto solo that his non-accompanying companions watch and listen to with as much pleasure and delight as the audience, before the other blowers and then the guitar take over, each with their own timbre and phrasing.

Beauty, generosity, sharing, quality and quantity… you name it! Jazz in Noyon was all this and more.

And the afternoon of Sunday, October 6, 2024 was a kind of concentrate of all that. A great jazz moment to remember. And why only one, you may ask? I’ll leave it to you to answer this thorny question asked in Oise this autumn.

——–

PS : Hats off to Philippe Laredo, director of Jazz in Noyon, and to his sonny, Lucas, vegetarian cook emeritus, who converted more than one of us to eating without meat nor fish.

PPS : The co-programmer of Jazz in Noyon is none but Jacques “Jack” Pauper, my favorite lider maximo — also boss of couleursjazz.fr —, without whom you’d know nothing about this festival since no other journalist bothered to come and cover it.

©Photos Jacques Pauper pour Couleurs Jazz

I would like to thank the autor of the article for his involvement in such a detailed report.

I used my imagination and moved there.I envy my stay at this festival,there are many musical and culinary attractions 😉