It’s sometimes said of old people that they won’t make it through the winter. This year, it’s spring when the Grim Reaper has decided to do his work, sending ad patres a splendid septet that we would have loved to see and hear on stage someday. We can dream, can’t we?

Two women and five men: Tina Turner and Astrud Gilberto, Harry Belafonte, Karl Berger, Ahmad Jamal, Wayne Shorter and Peter Brötzmann. Can you imagine this all-star line-up? Three voices, two saxes, a vibraphone and a piano: unprecedented and unheard-of! Those who believe in an afterlife will be convinced that these young departed will have reunited, as soon as they passed away, to joyfully celebrate their departure from this valley of tears, I’m sure.

But let’s take a look back at their time on earth.

Tina Turner, born in 1939 in Tennessee, deep in the American South, began her career performing rhythm ‘n’ blues and rock with her husband Ike Turner (an abusive husband she eventually left). Who doesn’t know their majestically slow then fast cover of “Proud Mary” by Californian rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival? She then embarked on a solo career, blending soul and pop to the delight of a large Black and White audience, earning her the title of “Queen of rock ‘n’ roll”. Although her music isn’t really my cup of tea, I had the opportunity to attend one of her concerts/shows in the ’80s, and I have to admit that she blew me away: insane energy, stage sense, impressive physical presence, muscular voice capable of sweetness… it was hard to resist this star’s charm!

Tina Turner, born in 1939 in Tennessee, deep in the American South, began her career performing rhythm ‘n’ blues and rock with her husband Ike Turner (an abusive husband she eventually left). Who doesn’t know their majestically slow then fast cover of “Proud Mary” by Californian rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival? She then embarked on a solo career, blending soul and pop to the delight of a large Black and White audience, earning her the title of “Queen of rock ‘n’ roll”. Although her music isn’t really my cup of tea, I had the opportunity to attend one of her concerts/shows in the ’80s, and I have to admit that she blew me away: insane energy, stage sense, impressive physical presence, muscular voice capable of sweetness… it was hard to resist this star’s charm!

Astrud Gilberto, a year younger than her American colleague, is a very different case. On the one hand, her voice was far less spectacular than Tina Turner’s, but most of her success was due to a few songs she recorded in the early 60s with Stan Getz and her husband of the time, Brazilian guitarist Joao Gilberto, whom she left for the American saxophonist while keeping her married name. After this resounding and lasting success (“The Girl from Ipanema” remains a timeless standard, and can be heard in an elevator, while shopping at Auchan – you prefer Carrefour? Suit yourself! – or quietly at home on your hi-fi system) the carioca singer’s career became fairly confidential, and she never regained the success of the early bossa nova tunes that flooded the airwaves and stages of the early sixties.

Now to the gentlemen: Harry Belafonte, to stay with the vocalists, is a phenomenon in his own right: singer, actor, activist in anti-racist social movements in the USA, friend of Martin Luther King… there’s no end to the number of hats he wears. Vocally speaking, he is equally eclectic. If his first successes were linked to calypso, a music he popularized worldwide, Belafonte is also an excellent jazz singer (I’d like to recommend his version of “Lean on Me” with full orchestra: a rarely played standard of which I know only two other versions, one by guitarist Tal Farlow in quintet, the other by drummer Shelly Manne in trio – hard to find better! – both already or soon to be heard on couleursjazz radio and reviewed on couleursjazz.fr by yours truly), and he also ventures into different types of repertoire: his version of “Dark as a Dungeon”, a country hit recorded by Merle Travis or Johnny Cash, is darkly dramatic and magnificent! The French pianist Jean-Michel Pilc, who lived in New York for many years, was Harry Belafonte’s artistic director alongside his jazz career, and he confided to me that this experience was very interesting for him musically speaking. With Harry Belafonte’s passing, we then loose a great American musician who, from his duets with Nana Mouskouri to jazz standards and calypso, displayed an incomparably broad stylistic palette.

Now to the gentlemen: Harry Belafonte, to stay with the vocalists, is a phenomenon in his own right: singer, actor, activist in anti-racist social movements in the USA, friend of Martin Luther King… there’s no end to the number of hats he wears. Vocally speaking, he is equally eclectic. If his first successes were linked to calypso, a music he popularized worldwide, Belafonte is also an excellent jazz singer (I’d like to recommend his version of “Lean on Me” with full orchestra: a rarely played standard of which I know only two other versions, one by guitarist Tal Farlow in quintet, the other by drummer Shelly Manne in trio – hard to find better! – both already or soon to be heard on couleursjazz radio and reviewed on couleursjazz.fr by yours truly), and he also ventures into different types of repertoire: his version of “Dark as a Dungeon”, a country hit recorded by Merle Travis or Johnny Cash, is darkly dramatic and magnificent! The French pianist Jean-Michel Pilc, who lived in New York for many years, was Harry Belafonte’s artistic director alongside his jazz career, and he confided to me that this experience was very interesting for him musically speaking. With Harry Belafonte’s passing, we then loose a great American musician who, from his duets with Nana Mouskouri to jazz standards and calypso, displayed an incomparably broad stylistic palette.

Karl Berger, one of the two European – and even German – members of this septet, is less well known. He is, however, a highly interesting multi-instrumentalist who, in addition to his favorite instrument, the vibraphone, also masters the piano. Born in 1935 in Heidelberg, he died on April 9 of this year, thus spoiling my birthday! He spent most of his career in the USA, where he rubbed shoulders with trumpeter Don Cherry – whom he met in Paris – saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Anthony Braxton, drummers Ed Blackwell and Jack DeJohnette, pianist/organist/composer Carla Bley… and was heavily involved in teaching activities at the Creative Music Studio he founded in Woodstock, New York. Little known to the general public (if there is such a thing as a “general public” in jazz), Karl Berger remains an interesting musician and an eminent figure in jazz from the 60s to the present day.

Karl Berger, one of the two European – and even German – members of this septet, is less well known. He is, however, a highly interesting multi-instrumentalist who, in addition to his favorite instrument, the vibraphone, also masters the piano. Born in 1935 in Heidelberg, he died on April 9 of this year, thus spoiling my birthday! He spent most of his career in the USA, where he rubbed shoulders with trumpeter Don Cherry – whom he met in Paris – saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Anthony Braxton, drummers Ed Blackwell and Jack DeJohnette, pianist/organist/composer Carla Bley… and was heavily involved in teaching activities at the Creative Music Studio he founded in Woodstock, New York. Little known to the general public (if there is such a thing as a “general public” in jazz), Karl Berger remains an interesting musician and an eminent figure in jazz from the 60s to the present day.

Peter Brötzmann is a multi-talented artist. Originally a painter, this native of Remscheid (1941) illustrated many record covers – his own, but not only – with his paintings. He is also a multi-instrumentalist, but more self-taught than Berger, who studied classical piano for a long time before turning to the vibraphone. Clarinetist, saxophonist (mainly tenor, but not exclusively), he also plays the taragot (a kind of double- or single-reed oboe or clarinet) and is best known for his enormous sound, torrential delivery and raging phrasing, which earned him the nickname “Machine Gun” and which became the title of one of his records. Deeply rooted in the free jazz scene in Wuppertal, Rhineland/Westphalia, where he settled early on and where he died in his sleep on 06/22, he collaborated with dancers like Pina Bausch and visual artists like Nam June Paik. A key figure in European free jazz from the late 60s to the present day, Brötzmann, often in the company of his friend bassist Peter Kowald, played with Dutch pianist Misha Mengelberg and his fellow drummer Han Bennink, as well as with British guitarist Derek Bailey. This didn’t prevent him from frequenting Americans such as Don Cherry, saxophonist Steve Lacy, Carla Bley, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, guitarist Sonny Sharrock… and, from the late ’80s onwards, musicians from the Chicago scene, where he created his Chicago Tentet. However, Brötzmann’s latest recording, released a few months ago on the ACT label, was recorded live in the company of American drummer Hamid Drake and Moroccan guembri player and singer Madjid Bekkas: a kind of world jazz that is difficult to classify and perfectly audible to ears allergic to free jazz. One characteristic of Peter Brötzmann remains to be mentioned: like many Germans of his generation – and not just musicians and artists – he was marked by Nazism and constantly sought to escape all forms of nationalism by exploring neighboring or distant lands, in Europe and across the Atlantic. With him, a major figure of modern and contemporary jazz disappears at the age of 82.

Peter Brötzmann is a multi-talented artist. Originally a painter, this native of Remscheid (1941) illustrated many record covers – his own, but not only – with his paintings. He is also a multi-instrumentalist, but more self-taught than Berger, who studied classical piano for a long time before turning to the vibraphone. Clarinetist, saxophonist (mainly tenor, but not exclusively), he also plays the taragot (a kind of double- or single-reed oboe or clarinet) and is best known for his enormous sound, torrential delivery and raging phrasing, which earned him the nickname “Machine Gun” and which became the title of one of his records. Deeply rooted in the free jazz scene in Wuppertal, Rhineland/Westphalia, where he settled early on and where he died in his sleep on 06/22, he collaborated with dancers like Pina Bausch and visual artists like Nam June Paik. A key figure in European free jazz from the late 60s to the present day, Brötzmann, often in the company of his friend bassist Peter Kowald, played with Dutch pianist Misha Mengelberg and his fellow drummer Han Bennink, as well as with British guitarist Derek Bailey. This didn’t prevent him from frequenting Americans such as Don Cherry, saxophonist Steve Lacy, Carla Bley, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, guitarist Sonny Sharrock… and, from the late ’80s onwards, musicians from the Chicago scene, where he created his Chicago Tentet. However, Brötzmann’s latest recording, released a few months ago on the ACT label, was recorded live in the company of American drummer Hamid Drake and Moroccan guembri player and singer Madjid Bekkas: a kind of world jazz that is difficult to classify and perfectly audible to ears allergic to free jazz. One characteristic of Peter Brötzmann remains to be mentioned: like many Germans of his generation – and not just musicians and artists – he was marked by Nazism and constantly sought to escape all forms of nationalism by exploring neighboring or distant lands, in Europe and across the Atlantic. With him, a major figure of modern and contemporary jazz disappears at the age of 82.

Now to the American jazzmen, in chronological order of birth.

Ahmad Jamal (born Frederick Jones in Pittsburgh in 1930: he didn’t convert to Islam and change his name until the ’50s) has been a jazz piano monument since the ’50s, when he started out as part of a piano/guitar/double bass trio, following in the footsteps of his elder, pianist Nat King Cole. He then switched to a piano/double bass/drums trio, and scored a huge hit with his version of the standard “Poinciana”, recorded live with Israel Crosby on double bass and New Orleans drummer Vernell Fournier. A trio and a recording that will go down in history as the supple pulsation of the bass and especially the drums, and the pianist’s sense of space and dynamics, were enthralling to listen to. It was shortly after this, in the late ’50s, that trumpeter Miles Davis expressed his admiration for Jamal’s playing, and asked his pianist, Red Garland, to draw inspiration from it. The dream of Jamal and Davis working together will never end, but the two were undoubtedly too strong personalities to get along, and both rarely appeared as sidemen. Ahmad Jamal’s career was not without its eclipses, and some American jazz critics even referred to him at one point as a “bar pianist”, which says a lot about the ears of these journalists and their brains, supposedly located between these two!

Ahmad Jamal (born Frederick Jones in Pittsburgh in 1930: he didn’t convert to Islam and change his name until the ’50s) has been a jazz piano monument since the ’50s, when he started out as part of a piano/guitar/double bass trio, following in the footsteps of his elder, pianist Nat King Cole. He then switched to a piano/double bass/drums trio, and scored a huge hit with his version of the standard “Poinciana”, recorded live with Israel Crosby on double bass and New Orleans drummer Vernell Fournier. A trio and a recording that will go down in history as the supple pulsation of the bass and especially the drums, and the pianist’s sense of space and dynamics, were enthralling to listen to. It was shortly after this, in the late ’50s, that trumpeter Miles Davis expressed his admiration for Jamal’s playing, and asked his pianist, Red Garland, to draw inspiration from it. The dream of Jamal and Davis working together will never end, but the two were undoubtedly too strong personalities to get along, and both rarely appeared as sidemen. Ahmad Jamal’s career was not without its eclipses, and some American jazz critics even referred to him at one point as a “bar pianist”, which says a lot about the ears of these journalists and their brains, supposedly located between these two!

Jamal also had a business career alongside his musical activities, and for a time owned his own jazz club in Chicago, where he had established himself. Jamal owes his comeback to France: in the early ’80s, he met a Parisian producer and was signed to the Dreyfus Jazz label, where he released a dozen CDs, including a tribute to one of his favorite French cities, entitled “Marseille”. French fans have thus had many opportunities to listen to this pianist’s incomparable playing live: power, mastery of dynamic contrasts, virtuosity inherited from classical music practice, great rhythmic ease… an Ahmad Jamal concert is always a treat for lovers of fine piano and of the “sound of surprise” that jazz is supposed to be. The only limitation, personal but shared by many of my colleagues, is that he was sometimes overly directive with his accompanists. He sometimes led them like an utter dictator, which could be embarrassing to observe. But Ahmad Jamal’s conception of the trio or quartet, with a percussionist in addition to the drums, likened him to a conductor who directs and drives every movement and evolution of the concert.

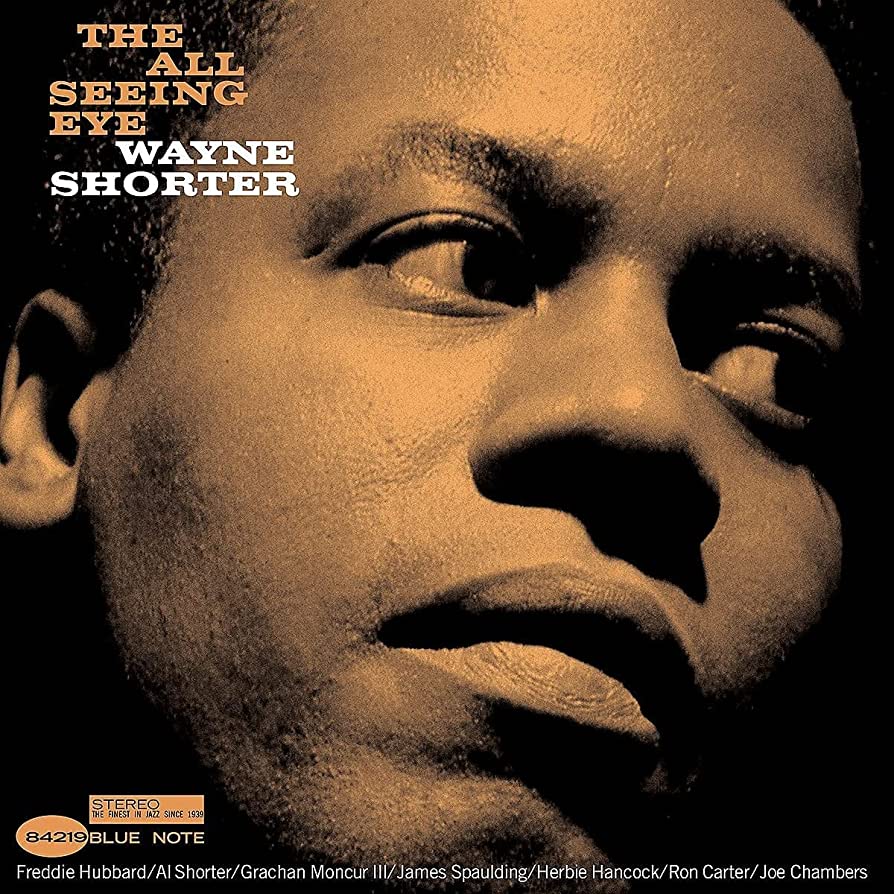

Of course, we have to mention Miles again when we talk about Wayne Shorter, who was born in New Jersey in 1933 and played in two of the trumpeter’s groups. But Shorter was originally a pure hard bop tenor who played with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. The drummer-leader soon entrusted him with the artistic direction of his combo, to which the saxophonist contributed some of his first compositions. When Miles Davis, having successively hired Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Hank Mobley and George Coleman as tenor saxophonists, was looking for a new blower, he poached Wayne Shorter from the Jazz Messengers to complete his historic second quintet. Here too, it was as a saxophonist and composer that Shorter distinguished himself, and some of his themes were long in the trumpeter’s repertoire: “E.S.P.”, “Footprints” and “Prince of Darknes” among others. At the same time, Shorter was pursuing a personal career on the Blue Note label, where his playing and writing were exemplary, with dark, even ominous titles such as “Armageddon” and “Dance Cadaverous”. A fan of science fiction, Shorter was also haunted by the supernatural.

Of course, we have to mention Miles again when we talk about Wayne Shorter, who was born in New Jersey in 1933 and played in two of the trumpeter’s groups. But Shorter was originally a pure hard bop tenor who played with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. The drummer-leader soon entrusted him with the artistic direction of his combo, to which the saxophonist contributed some of his first compositions. When Miles Davis, having successively hired Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Hank Mobley and George Coleman as tenor saxophonists, was looking for a new blower, he poached Wayne Shorter from the Jazz Messengers to complete his historic second quintet. Here too, it was as a saxophonist and composer that Shorter distinguished himself, and some of his themes were long in the trumpeter’s repertoire: “E.S.P.”, “Footprints” and “Prince of Darknes” among others. At the same time, Shorter was pursuing a personal career on the Blue Note label, where his playing and writing were exemplary, with dark, even ominous titles such as “Armageddon” and “Dance Cadaverous”. A fan of science fiction, Shorter was also haunted by the supernatural.

At the end of the 60s, he followed Miles Davis in his evolution towards a more electric jazz style, and took part — on soprano saxophone, which he played more and more — in two of the trumpeter’s major recordings : “In a Silent Way” and “Bitches Brew”. Then, with Austrian keyboardist Joe Zawinul, he founded Weather Report, one of the leading bands of the nascent jazz-rock movement, which lasted several years. Shorter then pursued a career that saw him play, for example, either with Brazilian Milton Nascimento or with his former colleague from Miles’ second quintet, pianist Herbie Hancock.

But his greatest achievement in the last years of his life was undeniably the Wayne Shorter Quartet, in which he surrounded himself with formidable musicians younger than himself: Panamanian Danilo Perez on piano, and Americans John Patitucci and Brian Blade on double bass and drums. The flexibility of interpretation and the ability to produce a moving, airy music of this quartet, in which Shorter often played very little, leaving the trio to express itself in total freedom, made it one of the leading groups of the early 21st century.

These springtime disappearances may leave jazz somewhat orphaned, but the influence of the members of this funeral septet is still very much alive, and we can bet that younger generations will keep it vibrating for a long time to come, while inventing new musical forms.

©Photo Header, Pixabay.

©Photo Couverture, Pixabay

RECENT COMMENTS