Pierre Favre is not a new comer. Yet his coming to Paris – and even more widely to France – is a major event, so rare is he on French stages that it’s scandalous.

So, when Hélène Aziza – one of his loyal fans – informs you that he’ll be performing at her magnificent venue at 19 rue Paul Fort, in Paris’s, in a duo with violinist Dominique Pifarély and then with one of the percussion ensembles he’s been renowned for for decades, you don’t skimp: you rush up.

For my part, I had the privilege of seeing Pierre – whom I hadn’t heard in ages – grant me a long interview on the balcony of 19 rue Paul Fort in the late morning.

Readers of Couleurs Jazz Media will discover it shortly by surfing the net.

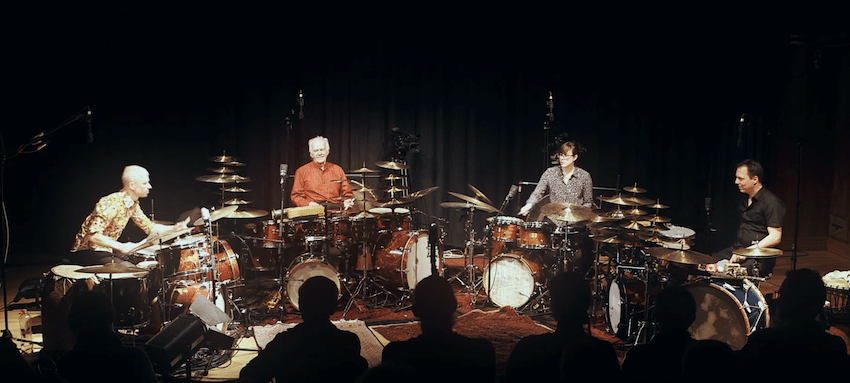

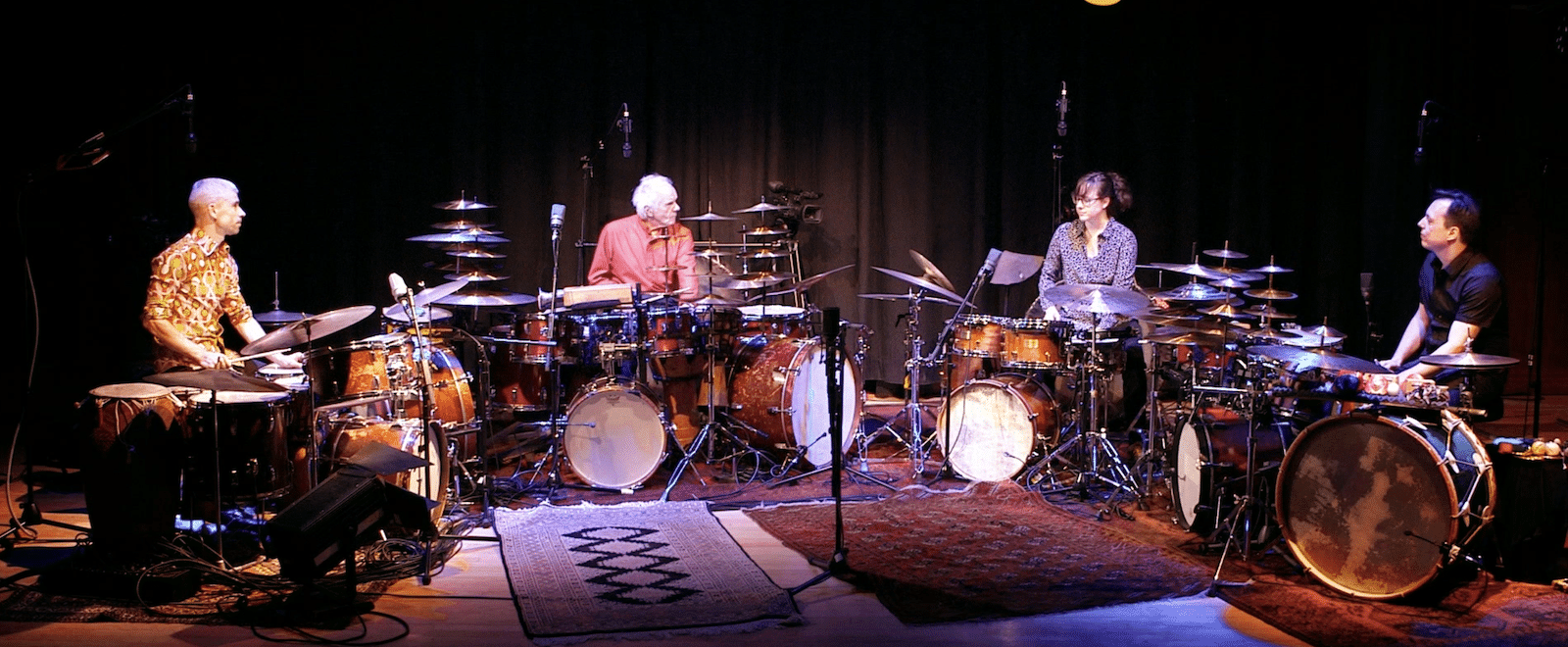

What’s striking about Pierre Favre is the multitude of toms and cymbals that make up his drum set. And when this set is multiplied by four for the performance as a whole, the astonishment borders on amazement. The result is feverish anticipation (what has he got in store for us?), because we know that with him you can always expect the best.

Favre starts on the gong, while Pifarély plucks or rubs the strings of his violin meditatively, while the drummer has switched to brushes on the snare drum and cymbals, and occasionally throws a bomb on the bass drum. Listening to each other is intense, and when the violin alternates spun tones and pizzicati, Favre switches to drumsticks, favoring the toms over the cymbals, which he uses randomly, before raising the tension with brushes rolls on the snare drum.

The violin then launches into little melodies of the finest effect, which he follows with an ostinato of great lightness in the high register of his instrument.

The next piece begins with the violin chirping over low drum rolls. It’s a kind of dance that the drummer sets up behind the melodic swirls of his partner. It’s a dance that’s both rhythmically crazy and very rigorous in its choice of sound. The drums sing their melody alongside the violin. Didn’t Favre call one of his recordings “Singing drums”?

As a percussionist-colorist, he opens the next piece with long, bean-filled beans wriggling on the snare drum and toms. Here, Pifarély launches into a high-pitched rubato melody, leaving the drums to keep the rhythm.

In the lamento that follows, on the violin, Favre discreetly echoes the cymbals with the mallets, then returns to the toms with the same delicacy, moving from one drum to the next with a great sense of melody and extreme gentleness, while the violin unfolds its own melody in parallel, also raising the tension in the fortes.

Then the ensemble’s three percussionists take the violin’s place, and we’re in for a sonic and rhythmic feast. It starts in the bass, with a kind of unison on the toms punctuated by higher-pitched strikes.

The overall sound is huge and gentle at the same time, swelling and un-swelling like a melodic-rhythmic wave that sweeps everything along in its path. You can hear a lot of Africa in this generous, collective flow, where each individual has his or her own place while integrating into the whole, whose undulations meander without it being easy to identify where the changes, accelerations or slowdowns are coming from.

This “beast with four heads, eight arms and eight feet” is fascinating to watch and hear unfold its ballet.

Favre begins the next track alone, resonating his gongs and cymbals before striking metal slats on the snare drum. Here we hear a sort of primal Indonesian gamelan as the bass drum hums and purrs.

Here again, the melodic construction is extremely strong, and the repetition of patterns punctuates the melody, which accelerates into a kind of trance that is both furious and controlled. It’s Markus Lauterburg — one of Favre’s young partners — who starts the next track alone, on almost classical drums were it not for the number of toms. Telluric rolls then play on the metal rings of the toms, while the other three join in, grafting little melodic-rhythmic cells onto the initial ostinato.

This is diversity in uniformity (or the opposite) at its best, and invention is born out of repetition.

The wonderful thing about Pierre Favre is that everything he composes and plays can be sung. That’s why his playing, and that of his fellow musicians, is so touching.

In addition to our interest in the construction of his pieces and their melodic and rhythmic aspects, they target the cantabile fiber in us that any listener who has ever sung in the shower or to lull his child to sleep carries within him.

And it is this primal, childlike yet mature fiber that is the substratum of everything this magician of sound composes or improvises.

In addition, Favre is an excellent leader who knows how to channel the energy of his fellow musicians and let them express themselves individually without his interference.

So, it’s Valeria Zangger and Chris Jaeger who take charge of the next track, unrolling a storm of rolls that end in a whisper.

Brushes take pride of place in the theme that follows, backed by a rumbling bass drum. It’s not every night that you hear four pairs of brushes dancing their dance on snare drums and toms, and it’s fascinating.

The drum/percussion duet that follows is equally fascinating, with its alternation of piano and forte. Favre possesses a great art of nuance, and nothing about him ever sounds like a gratuitous or ostentatious display of virtuosity.

Making music is his credo, and percussion is simply the means to that end.

The following track is a perfect example. Beginning with a low-pitched ostinato on toms and bass drums, it gradually evolves into an abundance of rimshots on the drum hoops, before returning to the original ostinato, which leads into a frisson of cymbals, before returning again, mixing low and high notes in an earthy rumble that seems never-ending. And that’s what we want.

Line Up:

Pierre Favre: drums, percussion

Dominique Pifarély: violon

Valeria Zangger: drums, percussion

Chris Jaeger: drums, percussion

Markus Lauterburg: drums, percussion

RECENT COMMENTS