Rather than writing yet another obituary, we have chosen to publish, in tribute to Michel Portal, who passed away on February 12 at the age of 90, an interview with the musician conducted in 2004 for the Italian magazine Jazzit, and therefore previously unpublished in both French and English.

His doubts and laughter, his enthusiasm and anger, old memories and new projects… Michel Portal speaks with the spontaneity of a young boy and the experience of an old man accustomed to the stage. Paradoxes and contradictions of a musician who, for more than 50 years, has been constantly exploring the world of music in all its forms. I see he has taken a lot of records from Universal’s press office, including a reissue of “Come Bach” by saxophonist Pierre Gossez, a typical piece of music from the 1960s.

Are you nostalgic for that era?

No, not particularly, but I knew this musician well, who is now almost forgotten. We played together in the studio for variety shows. At the time, we had a lot of gigs because we were good readers and because, if necessary, we could play in the style of Lee Konitz or Bud Shank…

We totally admired the Americans, we listened to them all the time, so if you were a good instrumentalist and had a good ear, it wasn’t difficult to imitate them. We saw so many of them play in Paris: Stan Getz, Johnny Griffin, Bud Powell, Chet Baker… What strikes me about that period, rediscovering this record by Gossez, is that he, like many others, never made it big, while others—like me—went on to have successful careers. In the years when we played side by side in the studio, we talked about money—because musicians often talked about money—or music, or women, but none of us thought about making a career out of it. We lived off music and didn’t try to make a name for ourselves.

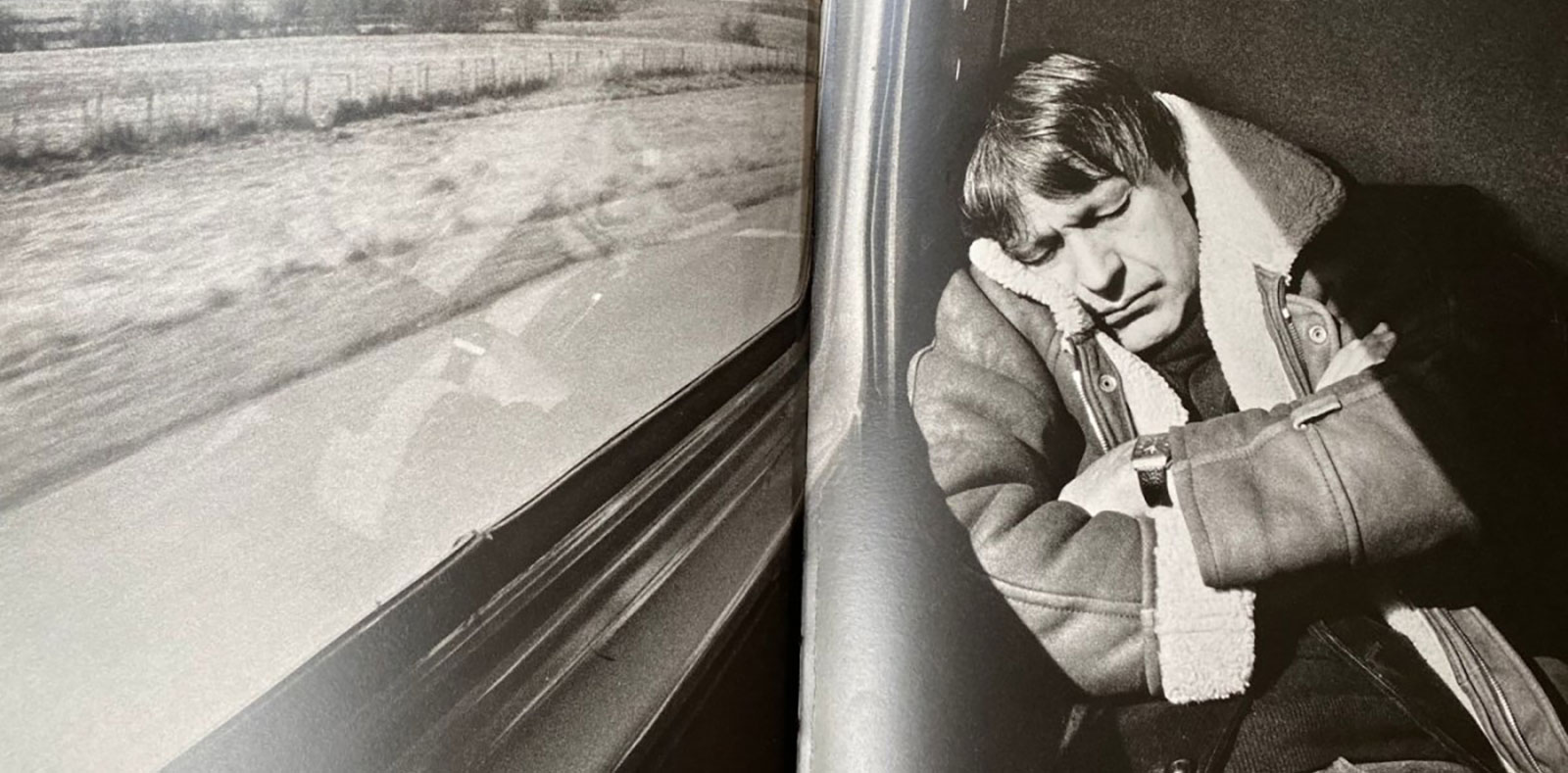

Hear Palmer 2010 by Michel Portal & Yaron Herman — © Guy Le Querrec & Sergine Laloux

What led you to move beyond admiring the Americans and become one of the leading representatives of contemporary French jazz?

It all started in May 1968 with the arrival in Paris of all these Black Americans who were playing free music: Archie Shepp, the Art Ensemble of Chicago… They were here, we saw them, we listened to them play, and we could play with them without having to be sidemen. They were totally open to sharing their ideas about their playing and encouraged us to draw on our folklore. It really opened up new possibilities for me, as well as for Henri Texier, François Tusques, Bernard Lubat… It was a time when community and sharing were very much in evidence. After all, that’s precisely why I called the group I founded at the time “Unit,” with whom I recorded that famous album at the Châteauvallon festival in ’72.

It was also during this period that I began to meet other European musicians who were part of this movement: John Surman (s), Albert Mangelsdorff (tb), Pierre Favre (dm)… Everyone, more or less, was looking for something along the same lines. But I quickly grew tired of this collective dimension. I soon became convinced that what I had composed up to that point, or to which I had contributed greatly, belonged to me and that I could therefore put my name to it. From that moment on, because of my view of things, I began to be looked down upon, and some colleagues still hold it against me. There was a lot of talk about the collective, but a few problems with money and copyright were enough to break up this beautiful unity.

Today, you mainly play this “free” game in a duo with Bernard Lubat, as shown on a recently released DVD.

That’s true, and we have a lot of fun, which isn’t always the case with young musicians or with those of my generation who have become “institutionalized.” Lubat and I are very different: he is very interested in social and political issues, he is prone to provocation, whereas I never express myself verbally during our concerts. It’s not that I think about it less, but if I expressed what I feel, I could be very violent and attack the audience, because the current era bores or disgusts me in many ways, and if I started talking about it, I would be capable of going very far. With Lubat, we assigned ourselves roles, a bit like circus clowns: one gets excited and makes the audience laugh, the other remains calm, naive, or dreamy.

Earlier you were telling us how you met your European colleagues, but in recent years your collaborations seem to have been more oriented towards American musicians: Jack DeJohnette, Joey Baron, Michael Bland and Sonny Thompson, or Tony Malaby on your latest album…

It’s curiosity that draws me to them. The French environment bores me a little, and I’m always looking for new partners to stimulate me: recently, Israeli pianist Yaron Herman; a few years ago, guitarist Sylvain Luc, who, like me, comes from the Basque Country. When they are suggested to me or when other musicians come to meet me, what attracts me most is the sound, the approach to music. Americans are so professional that when you suggest something to them, they assimilate it immediately and from there you can then develop things. Once they understand the piece, they make it their own and come up with their own ideas. So, there’s a real exchange throughout the concert, even though I know there’s no chance they’ll call me back after they return to the United States or after I leave, if I’m the one who went to record with them. The other interesting aspect is that they don’t know me, they don’t feel handicapped by comparison with a “legend of French jazz,” a definition that weighs heavily on me. I think that my wanderlust, my insatiable desire to explore, partly explains why I’ve never worried about my career and why I’ve never stayed with a band for very long. I am dissatisfied by nature, never satisfied with myself, and these doubts—which are not always easy to live with—keep me in a state of constant searching. The other aspect is that I hate being bored, and when that happens, I start looking for something new and stimulating.

Could that also explain your multi-instrumentalist side? From the clarinet to the saxophone, to the bandoneon…

It can mainly be explained by my curiosity and interest in travel, whether real or imaginary. A neighbor played the bandoneon when I was a kid in Bayonne. I loved the sound and the look of that box full of buttons, so I started hanging around when he played and he ended up teaching me the basics. After that, I continued on my own, before taking lessons with an Argentine teacher. But it was the same with the drums and the double bass, which I also studied at the conservatory. I was interested in any instrument I could get my hands on, and I always managed to get something out of them. At school, however, I did nothing; I was bored to death. What they wanted to teach me didn’t inspire me or take me on any journeys.

And was it always your curiosity that drew you to different types of music? Few other musicians play classical, contemporary, and jazz music like you do, not to mention studio work for pop music or dance when you were younger.

I like challenges; I don’t like staying in one place. Switching from the alto saxophone for a variety show to the clarinet for a Mozart concert was a challenge that stimulated me. That’s also why, even today, I want to remain at the highest level of instrumental practice, ready if you call on me to take on a difficult score, because I feel capable of playing it. I practice every day for hours on the instrument to maintain the physical fitness that is essential for my fingers and lips to respond to what is asked of them. And it is exactly this attitude that I respect in musicians like Tony Malaby. When he arrived at the studio, he had already worked on a difficult piece that I had sent him some time before. Once there, the technical aspect was no longer a problem and we really began to exchange ideas. In France, I find that young people are much lazier. Once they graduate, everyone wants to become a leader and make a record right away, but few of them really work on their instrument at a high level. I know that by saying these things, I sound like a grumpy old man again, but I’ve experienced times when the relationship with music was very different, even though I’m not particularly nostalgic.

We haven’t yet discussed one aspect of your profession—one that you seem to have put aside for some time now—film score composition.

I got into it through a few encounters, and even then, it was the novelty that attracted me. But it can be very restrictive work: you’re asked to create 12 seconds of suspense, and you have to use the usual clichés of action movie music in such a small space that anyone could have done it in your place. Once you’ve done it two or three times, you learn the tricks, and then it’s no longer interesting. On the contrary, when Nagisa Oshima [for his film Max Mon Amour, starring Charlotte Rampling] tells me to think of a landscape whose characteristics he himself describes, and to create a soundscape based on that, we’re in another dimension: there’s real work to be done, involving poetry and imagination. But not all film or documentary directors have this stature. In a short time, I gained a reputation for being good in this field because I’m a perfectionist, and many people called on me. I also gained a certain amount of recognition, but since I never went to collect the awards, because I hate that kind of ceremony, people in the world of soundtracks started to say bad things about me, and as a result, they called me less and less…

But you don’t like belonging to any particular circle…

That’s true. It seems that’s just the way I am: I write film scores that are well received, but then I distance myself and don’t go to collect my award. I play with European free musicians, but I disagree with them because I want to sign my compositions. I go to Minneapolis to record and French critics violently discredit my album and say that I despise French jazz… I know I have a bad temper and that I can be very difficult to deal with, but I think I’m honest in my own search for novelty. My problem is a bit like that of nomads compared to sedentary people: stable people, who form clans and castes and build cities, don’t really like gypsies who make noise, party, and are unstable… In the times we live in today, we are less and less inclined to party and have fun, and more and more inclined toward stability. You see, for example, I don’t have a cell phone or email. That’s my choice: I have nothing to do with these gadgets. And yet I’m still the same. If someone wants to hire me, they do what they have to do to find me, and they find me!

Ref : The outstanding photography book by Guy Le Querrec, reviewed here.

©Photo Header by Quy le Querrec

©Photo Cover by Jacques Pauper for Couleurs Jazz

RECENT COMMENTS