Jazz, like baroque and classical music, is fond of “themes and variations”, from Bach’s “Goldberg” to Janaceck’s “Tema con variazioni”, passing through Beethoven’s “Diabelli” or Brahms’ “Paganini”.

In jazz, some obsessives such as John Coltrane or Lee Konitz have recorded many versions of “My Favorite Things” for one, of “All the Things You Are” for the other.

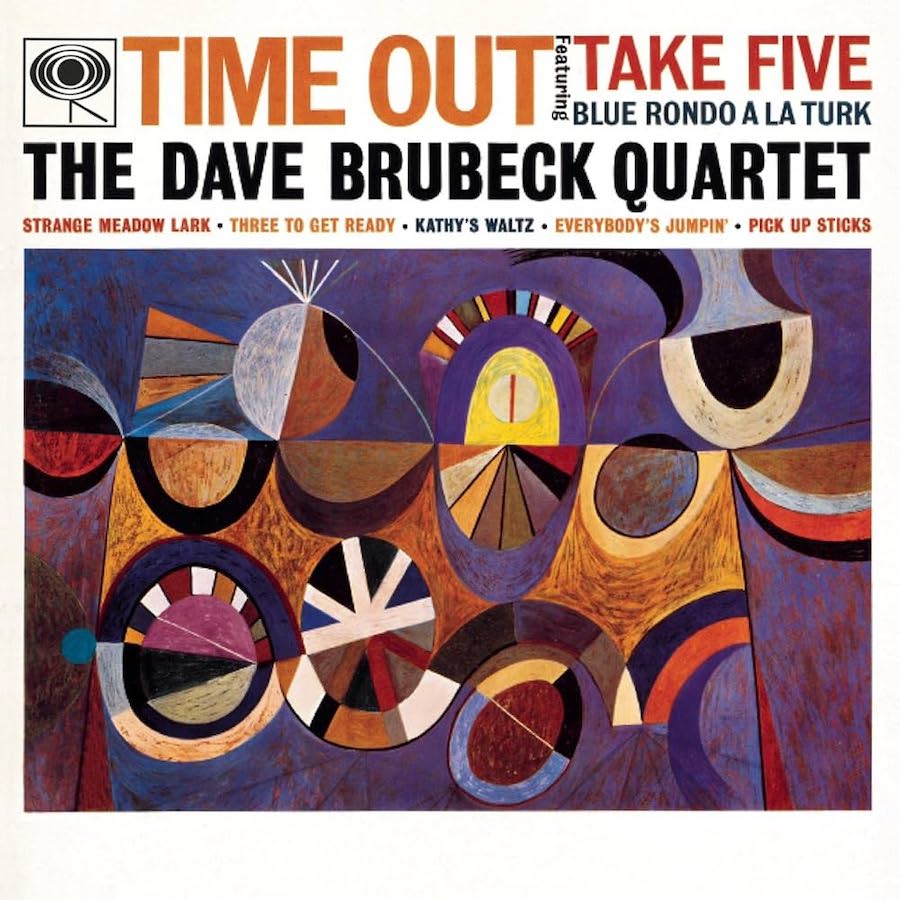

Today, I would like to tackle a modern standard that has gone far beyond the circle of jazz lovers: “Take Five” by Paul Desmond (and not by Dave Brubeck as some still believe because it was originally recorded by the pianist’s quartet in which Desmond played the alto saxophone).

Everyone was able to familiarize themselves with the five-beat rhythm thanks to this “hit” and everyone memorized the little melody that is set to this odd rhythm.

There is no need to comment on the original version, which is so well known that it has almost become a cliché. But let’s see what Quincy Jones has done with it, to begin with, in a large formation of course.

He starts with the drums and the bass which impulse to the five beats a supple wiggle before the trombones enter progressively by harmonizing the riff on which the rest of the orchestra grafts a subtle counterpoint.

Already the tube is metamorphosed and when the saxophone section intones the beginning of the theme we are clearly in another landscape. Especially since this theme will be cut into melodic slices to which sumptuous trumpet/trombone riffs answer.

It would be tedious to describe in detail the magnificent work of orchestration crafted by Quincy Jones. Let’s just notice that on Phil Woods’ alto solo, essentially supported by the rhythmic, he grafts brass interventions that punctuate the unfolding of the chorus (which is not at all reminiscent of Desmond’s original) until an unexpected vibraphone comes to give the sound space an almost spectral dimension. This is orchestral haute couture, and Quincy Jones has the art of infusing the unexpected into the known.

The last genius find: when the theme resurfaces, Quincy Jones echoes a portion of the melody, creating an effect of suspense that makes us wait for the next part, and it is the entire orchestra that will take up this melody that gradually disappears as if by magic.

(Album “Quincy Jones Plays Hip Hits“/Mercury – 1963):

At the antipodes of this version in technicolor sound and in large formation, we find that of Rhoda Scott whose Hammond organ is simply accompanied by a drum set which is not particularly in front. Here, it is the excellent organ solo, full of groove, which serves as a piece de resistance to this short and brisk interpretation of less than 3 minutes supported by a dense drumming. Rhoda Scott makes the hit her own by staying true to the melody but transposing it into the style of her instrument, and Take Five is so malleable that it lends itself easily to this fast and vigorous treatment.

(Album Rhoda Scott – “Take Five”/Verve – 1991)

Al Jarreau, on one of his most famous public recordings, begins with an almost whispered scat to which he gives a supple and tonic pulse before his sidemen on keyboards and vibraphone come to support him while he begins to sing the lyrics. The drums remain rather discreet here because it is the singer’s voice that takes care of the rhythmic and melodic aspect of this inhabited interpretation where Jarreau constantly varies the intensity of his singing by passing continuously from a terribly inventive scat to a taking charge of the lyrics. One remains totally mesmerized by the inflections and the melodic-rhythmic turns of this voice, both supple and powerful, which can allow itself anything on a song that it transforms.

(Album Al Jarreau “Look to the Rainbow“/Warner Bros.Live 1977)

George Benson, with a reel of his rhythm guitarist, gives Take Five a funky dynamic that will be maintained throughout the piece.

On this substrate, the solo guitarist states the melody note for note with a relaxed phrasing and an inimitable roundness of sound. It is then the solo of the leader which will hold all the attention: a flow of brisk and strongly accentuated phrases scrolls with a staggering melodic invention. One does not recognize the melody any more since Benson made this version his own, and when the electric piano takes over from the guitarist the interest obviously drops. One could wish that this version, which lasts more than seven minutes, were more concentrated on Benson’s solo, but the guitarist – who intervenes again in a less interesting way towards the end -, although an excellent soloist, does not have the dimension and talent of Jones or Jarreau as a “sound director” (as we say stage director in the theater).

(Album George Benson “Bad Benson“/CTI) or

Paul Desmond himself was not a big fan of his “hit” whose success had overtaken him a little. So much so that he later composed an ironic “Take Ten”, which is quite interesting partly because of the participation of guitarist Jim Hall.

However, the saxophonist came back to his favorite piece in the mid-70’s with his own band: a guitar (Ed Bickert), a bass (Don Thompson) and drums (Jerry Fuller), all on a nonchalant tempo perfectly corresponding to the one who called himself “the slowest alto sax on the planet”.

It is clear that Desmond wants to distance himself from the original version. In addition to his own Arabian style solo, the bass is given the leading role and it must be admitted that this late live version (Desmond died two years later at the age of 52) is a welcome departure from the one that made the success and the reputation of its author.

(Album “The Paul Desmond Quartet Live“/ A&M-Horizon- 1974)

RECENT COMMENTS