In 1999, producer Michael Cuscuna, co-founder of the Mosaic Records label in 1983 and responsible for Blue Note reissues in the 1990s and 2000s, who left us for good on April 20, 2024, told me the story of the Blue Note label.

When Blue Note began in 1939, it was the third-largest independent jazz label in the USA. All recordings of all kinds of music were produced by three major companies. In 1938, Commodore made its debut, followed by Chess, and finally Blue Note, the third independent American jazz label.

It all began with German-born Alfred Lion, who moved to the United States at the age of 17. He discovered jazz in Berlin and fell in love with it. He moved to the States to try and find work. He worked on the docks, sleeping in Central Park. But he didn’t want to continue. He returned to Germany in 1930. With his friend and neighbor Francis Wolff, he imported and exported jewelry to Spain.

But he wanted to return to America, and spent several years in South America. He worked on ships. This is part of the Blue Note story. As Alfred Lion was Jewish, he was a German refugee in America. In fact, he had left Germany before Hitler was elected. Eventually, he left South America for the United States in 1936. He attended jazz concerts as often as possible and built up a record collection.

In 1938, John Hammond organized a concert at Carnegie Hall called From Spirituals to Swing. Alfred Lion was so impressed by the boogie-woogie played by Albert Ammons, Meade “Lux” Lewis and Pete Johnson that two weeks later, he organized the first Blue Note recording session with them.

What had happened was that many musicians who played in clubs weren’t making records. Music was becoming increasingly sophisticated, especially with the big swing bands. Alfred Lion listened to the jazz being played in clubs like Café Society. He set up his own label to immortalize what he heard live in the clubs.

The second Blue Note recording session gave rise to an innovation thanks to an accident. He wanted to record an orchestra, but the musicians weren’t available. He came up with the idea of recording them at three in the morning, when the clubs were closed and the musicians free.

It was the only time when musicians could record together.

Alfred Lion thus invented the first “after-hours” recording session. Alfred Lion was especially fond of the traditional jazz of the ’20s. He began recording the masters of boogie-woogie, and then Sidney de Paris, Sidney Bechet and Edmond Hall, excellent musicians who had emerged from the New Orleans-style scene.

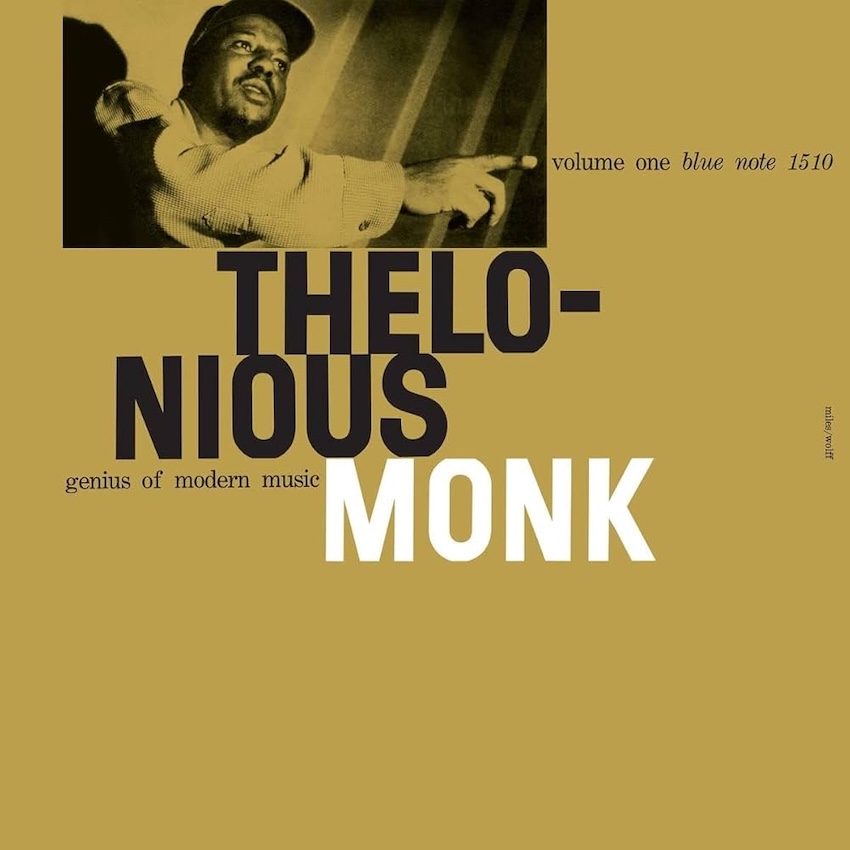

Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, Art Blakey…

During the war, Alfred Lion was drafted into the U.S. Army. But, fortunately, he got no further than Texas. Alfred with a gun is a scary thought (laughs).

His friend Francis Wolff had stayed behind in Germany, joining him later to work with him on Blue Note.

When the war started, Francis was working with Milt Gibler in the Commodore record store. After the war, jazz began to change. He recorded small swing bands, people like Tiny Grimes, Ike Quebec and John Handy. Ike Quebec introduced Alfred Lion to modern jazz in 1947. He introduced him to Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey, Bud Powell and Fats Navarro. Alfred quickly fell in love with modern jazz.

He recorded as much modern jazz as possible. In those days, Blue Note was still an independent label that enjoyed a certain degree of success. In fact, it lived from day to day. When the 78 rpm record came out in the ’40s, Blue Note was living because it couldn’t afford to invest in this new record industry.

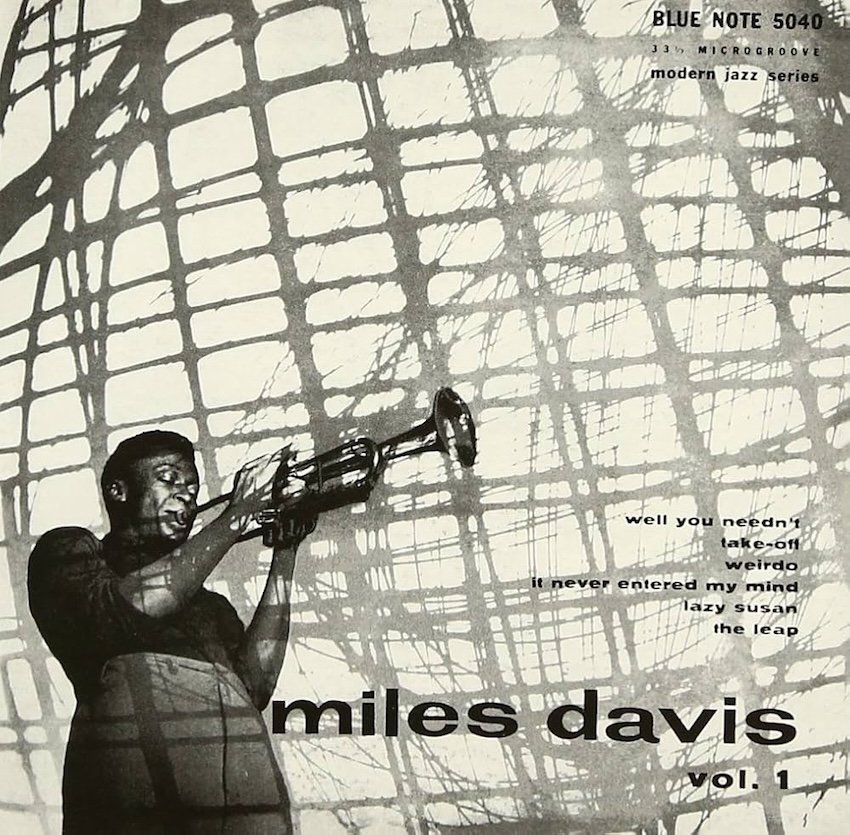

Even today, in 1999, recording a record is expensive. Alfred Lion fought to be able to record modern jazz. The label was recording a lot of quality sessions with Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Miles Davis, but in the end, it was a very tough fight he had to fight. At that point, something happened: Lou Donaldson was supposed to make a record. But he couldn’t, because he had to leave New York. Alfred Lion suggested to Lou Donaldson’s pianist, Horace Silver, that he lead the session. Horace agreed. He recorded as a trio.

A few months later, Alfred asked Horace Silver if he wanted to record with a saxophonist. Horace agreed again.

An orchestra was formed with Art Blakey, Doug Watkins, Horace Silver, Hank Mobley and Kenny Dorham. By this time, in late 1954, the jazz scene was getting boring. Many musicians were imitating Charlie Parker. Horace Silver and Art Blakey felt the need to really bring the jazz audience back. So they composed a lot of songs with blues, gospel, things that the public might or might not relate to modern jazz.

This was the beginning of the Jazz Messengers. And it was also the beginning of the success of Blue Note records. What Horace Silver and Art Blakey did when they embarked on the hard-bop adventure was to create the Blue Note sound. They set the standards for the next twenty years, what I would call the golden age of Blue Note records.

The Blue Note sound

With the invention of the 78 rpm and the success of the Jazz Messengers, Blue Note truly became a recognizable label. Blue Note made it possible to record unique records. For this, we have to thank a saxophonist, Gil Malley, who introduced Rudy Van Gelder to Alfred Lion in 1953. Rudy Van Gelder was a sound engineer who had his own recording studio in his parents’ living room. He was really the sound engineer who was able to record the big sound of a saxophone or the sound of a drum set. The overall sound was very clear. You could hear the piano very clearly, you could hear the bass, and you could hear all the music in one perspective. It was also a very wide sound. Importantly, he didn’t need a hundred microphones to record; two were enough to capture the sound of a drum set. You could hear every cymbal clearly, every nuance. The sound he got was extraordinary. Rudy lit up the music. Rudy Van Gelder’s sound and the music of Art Blakey and Horace Silver and the others, along with record sleeves that showcased the beautiful photography of Francis Wolff, with graphics by Reid Miles, really made Blue Note an original label.

The Blue Note style

Reid Miles designed between 300 and 400 record sleeves. He wasn’t a jazz fan, he didn’t understand anything about jazz. He designed the record sleeves according to Francis Wolff’s photographs taken during the recording sessions. Francis Wolff had stayed in Berlin after Alfred Lion moved to New York. In Germany, he had studied photography. He became a professional photographer. Being Jewish, he had to leave Berlin for New York. When he started working for Blue Note alongside Alfred Lion, he got into the habit of photographing all the recording sessions.

In those years, photos were the main focus. Alfred wanted the recording sessions to be documented. Francis would take portraits of the musicians. It should have taken five hours, but he did them in an instant.

The quality of his photos was first-rate. The most amazing thing was that, by photographing all the sessions, it was the very first time that recorded music had been completely documented photographically. I don’t think it’s been done before, and I don’t think it can be done again.

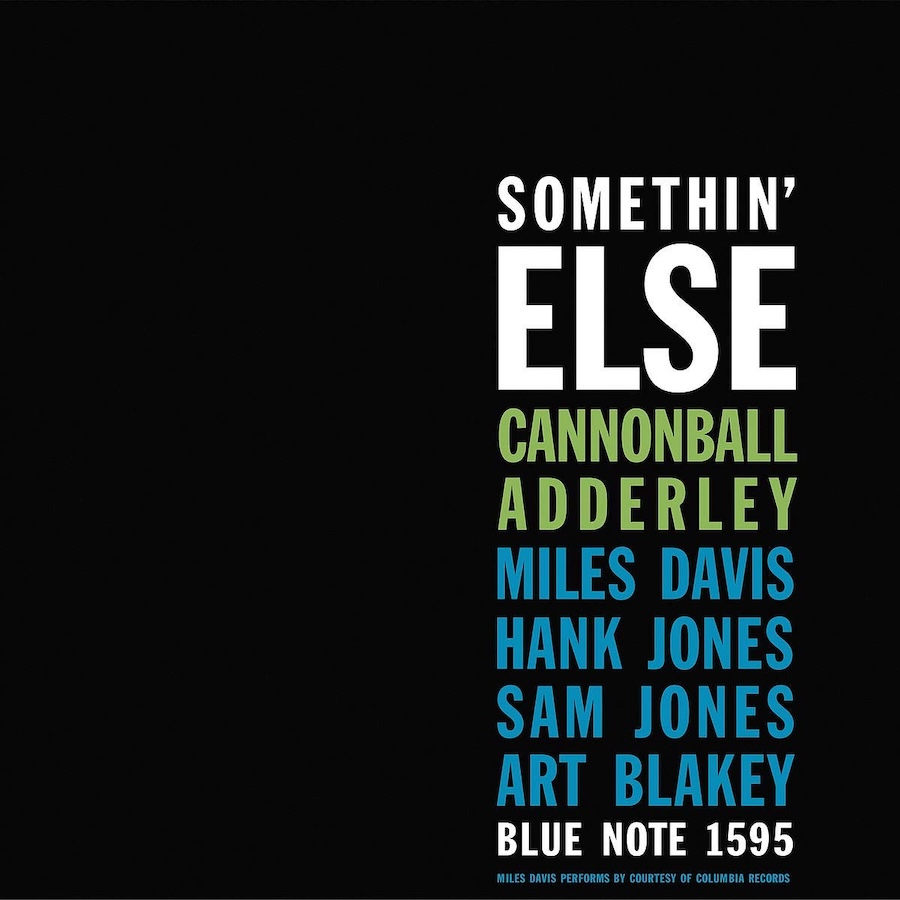

Reid Miles’ graphic design always captured the spirit of the album. Incredibly, every Blue Note record had a completely different design. Reid Miles had been greatly influenced by the Bauhaus. He had the great quality of integrating his graphic work with that of Francis Wolff. This made each record unique. He gave the album its color. Sometimes, the graphics were enough, like Eric Dolphy’s Out to lunch, with the photo of that door and that little clock going in all directions. That’s what happened with the music: time went in all directions. When I was a teenager, I wanted to buy these records because of their covers.

Blue Note thus became the quality label. Alfred Lion had an excellent approach to music, but he also knew how to record good albums when other labels would just bring musicians into the studio and have them record blues and standards. Alfred would talk to the musicians, ask them who the sidemen would be, and encourage them to compose. As a result, Blue Note records are far more inventive and organized than many other labels. He offered musicians good working conditions. Francis Wolff really made it possible for the records to be made in good conditions and to sound good. This was the Blue Note sound. This continued until 1967. There were many innovations, many changes. Someone like Jimmy Smith invented a new sound, that of the organ. Nobody had played the organ like him before. After him, many organists appeared, on Blue Note, but also Prestige, Chess and Savoy, various independent labels.

Jackie McLean, Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman…

Around 1962, the avant-garde began to become increasingly active. Alfred Lion became interested in new forms of musical freedom.

One of the musicians who greatly influenced him was Jackie McLean, who was very open to the new forms jazz was taking. Jackie introduced him to Tony Williams, Bobby Hutcherson and Grachan Monchur, and opened his ears to musicians like Andrew Hill. He also recorded Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry and Ornette Coleman. At the same time, hard bop musicians from the orchestras of Art Blakey and Horace Silver began to expand their vocabulary. Alfred Lion signed Herbie Hancock, who had been introduced to him by Donald Byrd. He also signed Tony Williams, Wayne Shorter and Freddie Hubbard. These musicians integrated the language of hard bop and then extended it, introducing highly complex modes and harmonies.

It was incredibly exciting music. It’s the music that made Miles Davis a hero in the mid-’60s. They became the new Blue Note standards. Joe Henderson, whom I forgot to mention, also played an important role. And so, hard bop took a new direction.

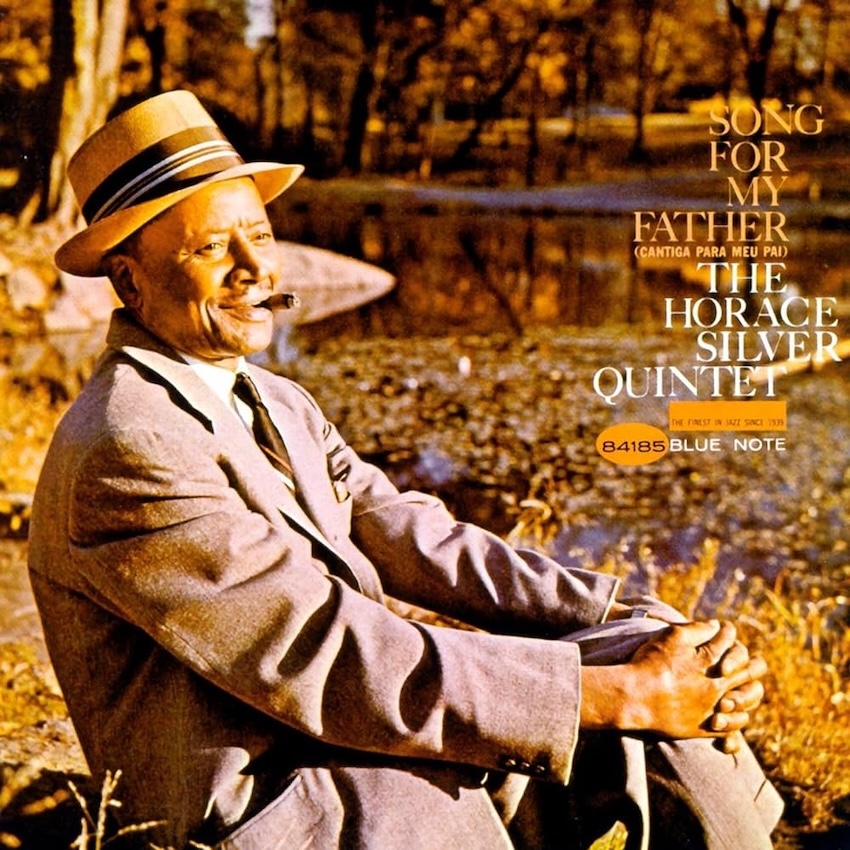

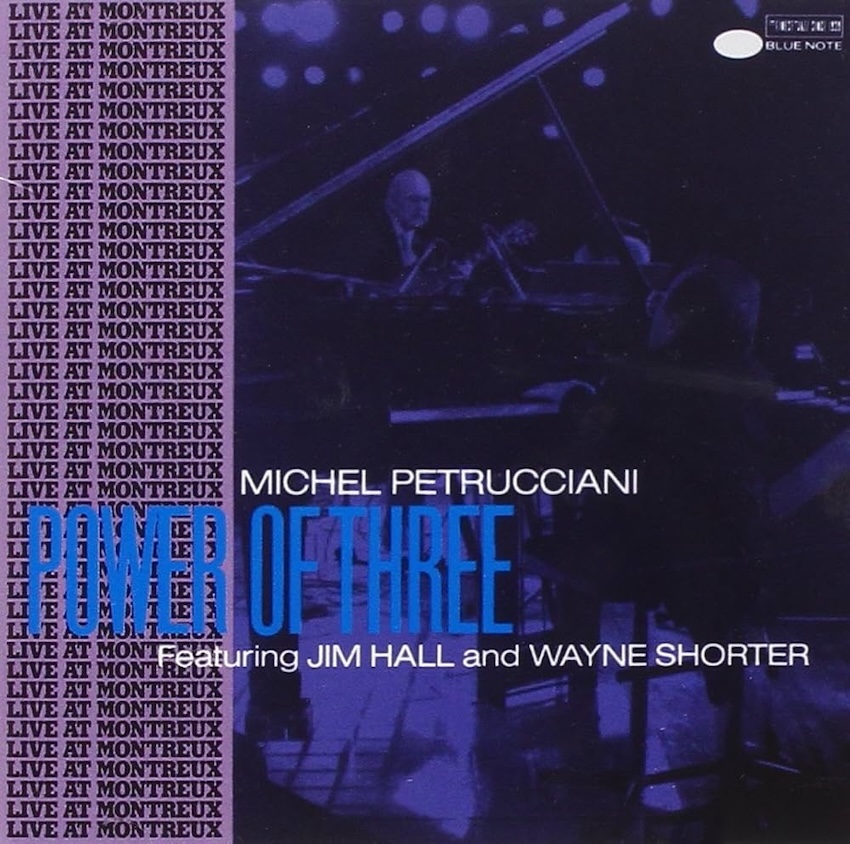

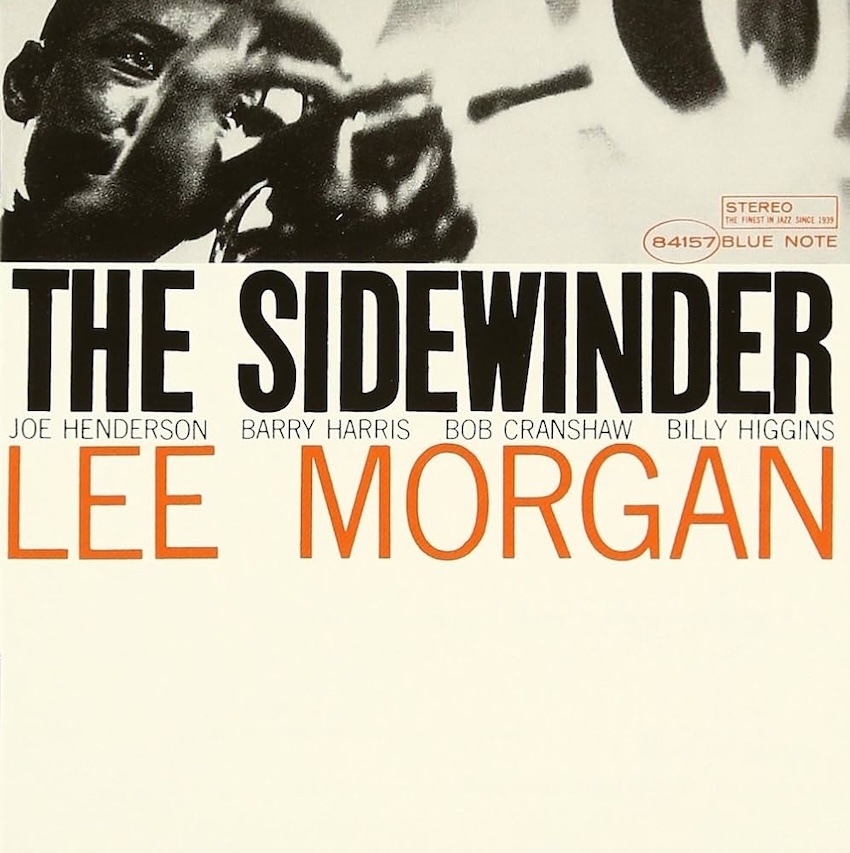

In 1965, Blue Note enjoyed great success with Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder and Horace Silver’s Song for my father. These were unexpected successes. If Lee Morgan and Horace Silver expected them to become hits, Alfred Lion didn’t think so. There’s something important to know about the record industry. If you get a hit, it becomes really problematic for a simple economic reason. If you sell a lot of records, you have to have other records pressed that you have to pay for within 30 days, and you have to pay royalties to the artists within 30 days. When you give those records to distributors to sell, you don’t get paid for 6 or 9 months. So the worst thing that can happen to you financially is to be successful, because you have to advance money before you receive it. This has become a major problem for Blue Note.

Alfred Lion realized that he needed the support of a larger record company. So he sold Blue Note to Liberty Records. That was in 1965, and it took a lot of stress off his shoulders. Running an independent label is great, but it’s more stressful than having ten kids. You don’t sleep, you can’t stop thinking about what you have to do… Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff sold Blue Note to Liberty Records.

The last sessions they organized were in June 1967. This also coincided with a change in the recording industry. FM radio was very popular in the United States. There were a lot of rock musicians on the music scene who were experimenting more. Alfred Lion produced funky jazz. Some of them were very successful at the time, like Lou Donaldson, Donald Byrd and Lonnie Smith. And he was still recording Ornette Coleman and Andrew Hill.

But when Francis Wolff died in 1971, Blue Note couldn’t go on.

Donald Byrd revived Blue Note in 1971 or 1972 with his album Black Bird, which had nothing to do with jazz, but was excellent pop music. The public was angry because Blue Note wasn’t what it was supposed to be.

But the world had changed.

Some artists stayed with Blue Note through the ’70s. Lou Donaldson left in 1975, Bobby Hutcherson in 1978, Horace Silver in 1981. He was the last living Blue Note artist.

That’s when I started reissuing the old Blue Note recordings. Eventually, the reissues stopped, and in June 1981, Blue Note came to an end.

Blue Note, the come back

In 1981, EMI approached Bruce Lundvall with the idea of setting up a pop label in New York. They didn’t have a label in New York, they were in California. Bruce is a big jazz fan. He had worked at Columbia and Elektra. He was asked to resurrect Blue Note. Bruce called me one day, asking me about reissues. I came up with the idea of an all-star concert paying tribute to Blue Note. The Town Hall concert was recorded and filmed. That same day, we released twenty reissues and one new recording, Stanley Jordan’s Magic Touch.

Bruce Lundvall and I continued to work together. I worked mainly on the reissues. As for the new releases, Bruce and I wanted to record the musicians who had taken part in the Blue Note classics. So we recorded Stanley Turrentine, Andrew Hill, McCoy Tyner, Kenny Burrell, Freddie Hubard, Woody Shaw and Joe Henderson. The new series of recordings was more of a crossover. We had to sell records. The idea was to find musicians who went beyond the usual jazz audience to reach a wider public.

Stanley Jordan’s Magic Touch was a great success, as were Bobby McFerrin and Dianne Reeves, as well as Lou Rawls. We didn’t make crossover albums, but records with artists who could extend the jazz audience, that’s the difference.

This was in the Blue Note tradition. Blue Note never made records like CTI or GRP. And when we were successful, it was thanks to the artists. Our other criterion was to find young talent. Jazz fusion became so important during the 70s that there were no young musicians emerging, with the possible exception of Wynton and Branford Marsalis, whose father, Ellis, is an excellent jazz pianist. There was very little young talent in New York. What we did was to create a new group, OTB, a Blue Note orchestra with a changing personnel. We auditioned 40 or 50 musicians, many of them excellent musicians like Lewish Nash, Kenny Garrett, Michael Philip Mossman and many others. These auditions were a great way to discover the new jazz scene.

So we worked along three lines: historic Blue Note musicians, crossover artists and young talent. This is still our approach today. Since then, the hip-hop phenomenon has appeared, with many rap groups sampling Blue Note records, which has been useful for us. We then reissued certain records on vinyl in the Groove series collection, which could then be played in clubs.

Blue Note, the Golden era of jazz?

There are many incarnations of Blue Note records.

I think that Blue Note, during its historic period, from 1955 to 1967, was the label that allowed jazz to develop in New York. New York wasn’t just a city, it was the jazz capital of the world.

Quality and consistency were brought to the fore, repertoires were built up, soloists became leaders. In my opinion, Blue Note represents the best sound documentation of the golden age of jazz. Dozens and dozens of giants recorded for Blue Note, most of them from New York. Today’s New York is relatively different. We still have the old Blue Note in mind. We make sure people still believe in Blue Note. We love the artists we work with, we try to make records with integrity with them. I think the new Blue Note is representative of today’s jazz.

Translated with the help ofwww.DeepL.com/Translator

RECENT COMMENTS