Carlos Don Byas (1913–1972) ranks among the greatest saxophonists in jazz history, as evidenced by the overall quality and variety of his discography.

His colleagues considered him an essential reference in tenor saxophone, and his virtuoso playing influenced figures of the caliber of Lucky Thompson, Johnny Griffin, and Benny Golson.

Yet his popularity with the public, though real, never matched his talent, which made him one of the most advanced jazz musicians of his time.

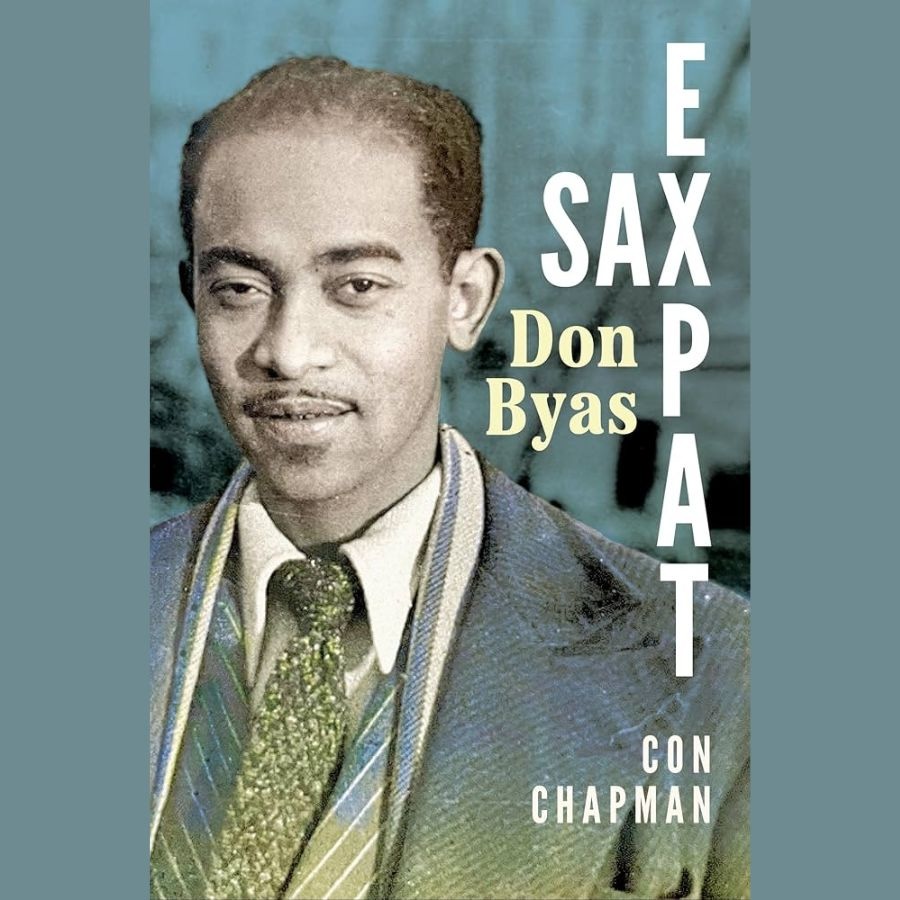

Drawing on an impressive bibliography and comparing his sources with the testimonies of those involved at the time, Con Chapman presents here, with the skill, objectivity, and erudition that ensured the success of his previous works, an objective perspective on the career of an exceptional jazz musician.

The first chapters of the book recount Don Byas‘s early days playing alto saxophone in the late 1920s with Benny Moten’s ensemble, and his time in California, where he perfected his art on the tenor saxophone with the bands of Lionel Hampton (1933), Eddie Barefield, and Buck Clayton (1936).

Don Byas was therefore an experienced musician when he arrived in New York around 1937 to accompany Ethel Waters with Eddie Mallory’s band. He quickly made a name for himself on the local scene, regularly attending jam sessions at Minton’s and clubs on 52nd Street, and recorded his first album at the initiative of Baron Timme Rosenkrantz, who would play an important role in his career.

Having become a popular figure on the local scene, he joined Count Basie’s orchestra in 1941, where he became one of the stars and, on November 17, recorded an anthology solo in Harvard Blues. In high demand, Byas collaborated with musicians of all stripes and produced numerous high-quality records for small labels. These include a superb interpretation of These Foolish Things with Hot Lips Page and a magnificent version of Laura, a ballad from Otto Preminger’s eponymous film, which has since become associated with him.

The author then analyzes Coleman Hawkins’ influence on his hero’s style, particularly evident in his voluptuous way of playing ballads and swinging passionately at a fast tempo, but also in his way of improvising on a sequence of chords that seem, at least at first glance, unrelated to the initial melody of the piece, all carried by his virtuoso technique.

Next comes the melodic invention inherited from Art Tatum, whose piano solos he reproduced on the saxophone, and the importance of sound, rightly emphasized by Pierre Voran: “Don Byas favored sound above all else: he would blow a single note, hold it, inflate it, full and magnificent. Each note was as beautiful as a cathedral.”

However, being considered Coleman Hawkins’ most gifted disciple meant that Don Byas would always remain in his shadow, which led to a feeling of frustration that would never leave him. Feeling that he was not properly recognized in his own country, he left for Europe in 1946 with Don Redman and his orchestra. Seduced by the welcome he received, he decided to stay.

After a stay in Spain, Don Byas settled in Paris, where he felt at home. Boris Vian devoted a humorous chapter to him in his book on Saint-Germain-des-Prés, in which he wrote: “…an incorrigible womanizer, he is easily prey to the fairer sex, for whom he has too many weaknesses…” In the summer, he was in Saint-Tropez, where he practiced spearfishing. He was also often seen in recording studios with the cream of French musicians and in the company of compatriots visiting the Old Continent, such as the great Mary Lou Williams, whom he met at Andy Kirk’s, and the seductive pianist-singer Beryl Booker.

In 1955, he lived in Amsterdam with his wife Johanna “Jopie” Eksteen and took part in the 1960 Jazz at The Philharmonic tour, which played to a full house at Pleyel. What followed was less happy. In 1970, a return to his native country proved disappointing. The man Johnny Griffin nicknamed the Art Tatum of the tenor saxophone died on August 24, 1972, of lung cancer. Carefully written, this book fills a gap in jazz literature by paying a fitting tribute to a great musician. It is therefore indispensable.

Translated with DeepL.com

Watch the Video ‘I Remember Clifford’ Live at the Village Vanguard – 1970

Con Chapman – Don Byas, Sax Expat

University Press of Mississippi, April 15, 2025

258 pages, 25 illustrations

* “Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges”, Oxford University Press Inc (2019), et “Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good”, Equinox Publishing Ltd (2023) de Con Chapman.

RECENT COMMENTS