…or that we don’t hear much, if you prefer.

In the “jazz” bins of the record shops – those that are still available in this world where music is more and more dematerialized – the female voices hold the top spot. Whether it is those of the divas or the minor voices of the past through reissues or those of the singers who are presented, rightly or wrongly, as their heirs: Madeleine Peyroux, Melody Gardot, Norah Jones… for the younger ones, Dianne Reeves, Cassandra Wilson, Diana Krall… for their elders. Not to mention our French voices: Anne Ducros, Elisabeth Kontomanou, Laïka Fatien… or more recently Mina Agossi, Lou Tavano, Cyrille Aimée, Leila Martial…

And the men in all this? For the dead veterans, (Mel Tormé, Mark Murphy, Andy Bey, Kevin Mahogany…) or alive, apart from Frank Sinatra, Nat “King” Cole and maybe Tony Bennett, their prestige is still below that of their female colleagues.

As for the youngest, three stars emerge from the lot: in the USA, Gregory Porter and Kurt Elling, whom I considered at first as a sub-Mark Murphy but who ended up convincing me that he deserved my esteem somewhat.

On the Old Continent, the youngest of the three is in the lead: Jamie Cullum, who often flirts with pop but remains a remarkable jazz vocalist when he wants to be.

So it is not these three stars widely covered by the media that I propose to talk about here, but the cohort – for there are many of them – of male voices that are little or poorly heard, particularly those that are flourishing in Europe.

David Linx, Thierry Péala, Loïs Le Van, Kevin Norwood, Manu Domergue... in France, Ian Shaw in the UK, the late Gabor Winand in Hungary, Grzegorz Karnas in Poland, Michael Schiefel in Germany, Andreas Schaerer in Switzerland… so many names of which not one reaches the notoriety of the aforementioned female singers.

Why this ostracism towards male voices? The main reason seems to me to be that high-pitched voices have always attracted the human ear more than low-pitched voices, in all kinds of music.

In the baroque period the vogue of the castrati is the most striking example and their “resurrection” through contemporary countertenors is the confirmation of it. From Alfred Deller to Philippe Jaroussky, from James Bowman to René Jacobs, there are countless high voices whose fame exceeds that of their baritone or bass colleagues. In the field of bel canto, tenors have always been more appreciated by the public than lower voices, and the stars in this field are more Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, Alfredo Kraus or Roberto Alagna than the baritones Dietrich Fischer-Diskau or Hans Sotin.

Among women, too, the sopranos are the most famous, and no contralto – except perhaps the late Kathleen Ferrier – can match the renown of Maria Callas, Marylin Horne, Montserrat Caballé, Jessye Norman or Barbara Hendricks.

It is therefore not surprising that this appetite for the high register can be found in the field of jazz. In this context, the male voice can seem “fragile” and unspectacular. In fact, except for the blues shouters who flourished in Count Basie’s orchestras (Big Joe Turner, Joe Williams...), male vocalists tended to cultivate a certain delicacy of tone.

Jimmy Scott, Johnny Hartman, Chet Baker or Andy Bey are good examples and all of them sang more in small formations than supported by the big bands where their female colleagues held the star.

Male voices in jazz have to overcome a few obstacles in order to impose themselves and it is in their interest to display a strong singularity in order to stand out in a landscape where virtuoso instrumentalists and female voices with their often spectacular timbres and phrasing dominate.

What male vocalist can compete with the impressive scat or range of a Sarah Vaughan, an Ella Fitzgerald, an Anita O’Day, a Betty Carter, a Dianne Reeves or a Cécile McLorin-Salvant?

With male voices, it is thus to something other than virtuosity that one must be sensitive and it is by their sensitivity that these gentlemen distinguish themselves particularly, most of the time.

On one of his many records (“One Heart, Three Voices“/E-Motive-2005), David Linx is flanked by Dutchwoman Fay Claassen and Italian Maria Pia De Vito. The three of them perform Cole Porter’s standard “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye” a capella.

It is delectable to savor the compatibility of these three timbres that alternate before closing the piece in unison. It is also fascinating to compare their version with the one of Sarah Vaughan (“After Hours“/Roulette-1961) in small committee (only Mundell Lowe’s guitar and George Duvivier’s double bass accompany her) or with the one of Betty Carter and Ray Charles (“Ray Charles and Betty Carter“/ABC-1961), two versions in slow tempo that our three Europeans know, of course.

Linx has chosen here to focus on the timbre of the voices by favoring an unusually slow phrasing. On the other hand, when he sings with the Portuguese vocalist Maria Joao with her extroverted personality and bouncing phrasing (“Follow the Songlines“/Naïve-2008), the Belgian singer deploys a more obvious power and uses more of his remarkable range. That is to say an expressive palette of which few of his colleagues are capable, which probably explains why Linx confronts more than them with female voices and is not afraid to be accompanied by large groups like the National Orchestra of Porto on the above-mentioned recording or elsewhere by the Brussels Jazz Orchestra. He has also recently recorded a duet with Belgian bassist Michel Hatzigeorgiou (“The Word Smith“/Sound Surveyor-2018): a perilous exercise that he manages magnificently and that, to my knowledge, no male singer had attempted before him.

Only a few female singers have ventured into this field, but with double bassists: Sheila Jordan with Harvie Swartz, Karin Krog with Red Mitchell and NHØP, Maria Pia DeVito with Silvia Bolognesi and more recently Jen Shuy with Mark Dresser, Rebecca Martin with her husband Larry Grenadier!

In his fifties, David Linx is a veteran among European jazz singers, some of whom have been influenced by him and some of whom have been his students.

Let’s have a look at these male voices from the Old Continent, starting with another young veteran (who was among others Jamie Cullum’s teacher): the Welshman Ian Shaw, born in 1962.

Three years older than Linx, Shaw has several similarities with the latter: on the one hand he likes to confront female singers such as the British Claire Martin or Liane Carroll, on the other hand he does not hesitate to join big bands.

But he is, more than his Belgian colleague, attracted by accompanists from across the Atlantic such as pianists Billy Childs or Cedar Walton (“In a New York Minute“/Milestone-1999; “Soho Stories“/Milestone-2001).

Shaw also composes less frequently than Linx and his repertoire of standards extends to contemporary pop compositions, by Joni Mitchell for example. He even goes so far as to include the hit “Human Nature” made famous by Michael Jackson, of which he gave a much more acoustic interpretation than Miles Davis (“The Abbey Road Sessions“/Splash Point-2011).

Ian Shaw has a warm tone, a flexible phrasing and an undeniable charisma and I almost forgot to mention the fact that he sometimes accompanies himself on the piano. One wonders why the French programmers don’t make him take the Eurostar more often to come and delight the ears of the French listeners!

Another British (originally from Avignon, but who spent his life in France) is Kevin Norwood. To introduce him, I momentarily pass the microphone to my old friend David Linx, who is the author of the liner notes of his first record (“Reborn“/Ajmiséries-2015): “Here is Kevin Norwood, a newcomer in the French vocal jazz landscape with a warmly high voice, a roundness in the sound that reminds us of the sweetness and swing of a young Betty Carter. The flexibility is surprising and the approach to improvisation brings us back to a male vocal jazz that has been neglected for some time, both current and imbued with a certain melancholy. He is accompanied by highly accomplished and creative young musicians who make the whole thing very coherent. A real band sound with vocalist Kevin Norwood as an integral part of it” writes David, who knows more than a little about it.

Not much to add to that except that Norwood composes the entire repertoire, lyrics and music, which is all the more remarkable because those lyrics and music are… remarkable! Here is a musician as much as a singer (he is also a trained instrumentalist, a saxophonist to be precise) who is worth the detour, all the more so as the band that accompanies him is first rate. His second album (“Hope“/Onde music-2021) with the same team, which uses here and there the electronic in a rather relevant way, shows a beautiful maturity because the voice gained in depth and in nuances. Moreover, Norwood leaves the trio that accompanies him some nice spots to improvise. It is not a record where the singer puts himself forward. He is integrated into a tight quartet whose empathy is palpable. Warmly recommended!

Grzegorz Karnas is a phenomenon. To give you an idea of where he stands, when he came to compete in the jazz singing competition of the Crest Festival (in the Drôme), a few years ago, he made the trip from his native Poland… by hitchhiking! Pretty ballsy, isn’t it? He won the contest, of course. Since then he has recorded quite a lot, in Poland (“Karnas“/Hevhetia-2011) or in Hungary (“Vanga“/BMC-2014), toured in Europe or in China, created a festival and a jazz singing contest in his hometown of Zory, near the Slovak border. A former mining town that nothing predisposed to see/hear jazzophile and singing crowds.

In short, Grzegorz is a resourceful man. And his voice? A rather high timbre, of a great softness or a great power, a surprising voice, even bewitching by its capacity to create the surprise and to mix with the instruments which accompany it, among which the cello of Adam Oles or the cymbalum of Miklos Lukacs. Grzegorz is a musician-singer who is really worth the detour and we are fortunately beginning to hear him in France and everywhere else where Voicingers has spread thanks to his creative and organizational energy.

Let’s cross a few borders to Hungary where another vocalist, also a saxophonist by training and unfortunately deceased a short time ago, resides: the singular Gabor Winand. Singular because when he does not sing words, he modulates in scat sometimes unheard sounds with a phrasing of a great flexibility and very interesting. On the oldest record of him that I possess (“Agent Spirituel” – in French in the text – published in 2003 on the label BMC), he is accompanied by a flock of Magyar compatriots, among which the excellent guitarist Gabor Gado.

On the second (“Different Gardens“/BMC-2004), idem, but the third (“Fabulas“, still on BMC, which means Budapest Music Center, in 2009) sees him flanked by two foreign musicians: the Cuban pianist Ramon Valle and the Dutch trumpet player Eric Vloeimans, two international stars that I won’t insult you by introducing you to. In this context – as on the above-mentioned CDs – Gabor Winand shows a beautiful inventiveness, masterly assisted by his Cuban-Batavian companions on a repertoire composed by himself or by Valle. A serious client, therefore, this Hungarian that we could hear a few times in France, but not often enough for my taste.

After this little tour behind the former iron curtain, let’s go back to the west! To Switzerland, more precisely where another phenomenon is rampant: Andreas Schaerer, whose throat and larynx conceal one of the most diversified vocal potentials that can be found.

Whether he’s singing lyrics, scatting or doing the human beat box, Schaerer has every chance to amaze and enchant you. The Swiss magician – who is also a composer and was a guitarist in his teens – performs in a variety of settings: with his regular band Hildegard Lernt Fliegen (Hildegard learns to fly in english), as a duo with his compatriot percussionist Lucas Niggli (“Arcanum”/Intakt-2014), in a large orchestra (arranged by himself), and more recently within a very high-flying European quartet completed by “our” incomparable Emile Parisien and Vincent Peirani and by the fabulous German pianist Michael Wollny (“Out of Land“/ACT-2017). It is difficult to say anything bad about any of these formations: Andreas Schaerer and his companions are irreproachable, inventive, exciting! Schaerer has also collaborated with many other artists, from Bobby McFerrin to the British saxophonist Soweto Kinch and the Finnish guitarist Kalle Kalima. To say that he’s being snatched up is an understatement! Anyone who misses out on the art of this wise and crazy Swiss man doesn’t know what he is missing and is frankly to be pitied. To deprive oneself of the pleasure of listening to this exceptional vocalist is properly a matter of the most pitiful masochism.

Let’s go to Germany!

There, Michael Schiefel is waiting for us. This young man in his fifties probably does not leave the borders of his native country as often as his Swiss colleague mentioned above, and his art does not have the same scope as the latter.

He remains however an engaging vocalist who frequently uses electronics to accompany his voice. Apart from his nice solo – in re-recording – (“Don’t Touch my Animals“/ACT-2006) and his recordings with the German band JazzIndeed, his most interesting records seem to me to be the ones he recorded in Budapest: the one that pairs him with fellow Hungarian pianist Carsten Daerr and two Hungarians, the excellent bassist Matyas Szandai and the superb cymbalum player Miklos Lukacs (“Gondellied in Sahara”/BMC-2010) and the trio he forms with the same Lukacs and the magnificent cellist Jörg Brinkmann (“Platypus Trio“/BMC-2014). Since then Schiefel has recorded several CDs for the Traumton label among others but I only had the opportunity to listen to a few extracts on the net, which confirmed to me that this singer is a safe bet.

Back in our dear Hexagon! We meet Thierry Péala, an almost veteran of jazz singing in France, who teaches a lot – like David Linx, Loïs Le Van or Manu Domergue – and thus transmits his passion of singing to new generations of vocalists.

I own three of his records. On the first CD (“Inner Traces“/Naïve-2000), he devotes himself to compositions by Kenny Wheeler, which is not frequent for a vocalist. He also invites Wheeler to join him on some tracks (on flugelhorn and trumpet) as well as his frequent partner, the great British singer Norma Winstone.

In addition to the originality of the project, we can immediately see where Peala‘s aesthetic lies: an intimate and melodic jazz where his voice of a great sweetness – but not without tone – works wonders and where his supple scat is a delight.

On this recording, as on the next two, he is accompanied by the excellent pianist Bruno Angelini, who composes most of the repertoire. On “New Edge” (Cristal Records-2007), the two companions are joined by Sylvain Beuf on saxophone and on “Move Is” (re: think-artrecords—2011) – whose theme revolves around the cinema – it is Francesco Bearzatti who completes the trio on tenor and clarinet.

That is, in both cases a delicate and tasty chamber music, never devoid of punch. Thierry Péala is clearly a voice to follow since he started recording at the beginning of the third millennium.

Loïs Le Van, younger than Péala, has a particular story with me. Indeed I discovered him a few years ago in Poland during an edition of Voicingers, the jazz singing contest organized by Grzegorz Karnas where Loïs was the only male vocalist. I was on the jury of this contest with the American pianist-singer Patricia Barber and the Swedish bassist-cellist Lars Danielsson. I didn’t really like Lois’ voice: too high-pitched, too “feminine” for my ears… And as he and I were the only Frenchmen present at this edition of Voicingers, I apologized to Lars and Patricia for the first performance of this singer which didn’t satisfy me.

My two colleagues of the jury looked at me like if I was a UFO and said to me “But you’re kidding, Thierry, this singer is very interesting. He’s even the most original of the lot!”

These two musicians gave me a good lesson and flipped me over like a pancake. I started to pay more attention to Loïs Le Van‘s phrasing and inflections, forgetting what bothered me about his tone. And he won the competition unanimously.

Since then, Loïs Le Van has had a great career (which I’ll let you discover on his website) and, although I still have problems with his tessitura, I recognize that he is one of the most original and interesting voices to have emerged in Europe in recent years.

Manu Domergue, on the other hand, has the particularity that when he is not singing in his band Raven, he plays the mellophone, a rare and sweet brass instrument popularized by Stan Kenton in his aptly named “Mellophonium Band”… not to mention Don Ellis and some others.

This instrument, close to the flugelhorn and the French horn, has obviously had an influence on Domergue‘s voice, whose phrasing is remarkably fluid and whose tone alternates between sweetness and pugnacity in an impressive way. Manu has a rather atypical background. A student of the great Brazilian singer Mônica Passos, he also went to California to study with the singing pedagogue Roger Letson – like Loïs Le Van – and he also went to make a name for himself via the Voicingers singing competition in Poland. He has been the French relay of Voicingers for a few years. “Chercheur d’orage” (Gaya—2013), the first CD of Raven, Manu Domergue‘s band, is simply amazing. The singer officiates as a vocalist, lyricist, composer and arranger. The name of the band comes from a Joni Mitchell song (there are worse references!) and the instrumentalists who accompany Domergue are all excellent and have been following him for years.

I don’t own Raven‘s latest CD, (“The One Who Fled His Shadow“/ Free Scene-2018) but what I heard of it on the net delighted me.

We can see that it is above all on the Old Continent that the art of male jazz singing has developed, and this for barely three decades. Even if their success does not reach that of their most prominent female colleagues, these male vocalists have found their audience and transmit their art – to young people of both sexes – in conservatories, jazz schools and workshops that are very successful. The festival coupled with a jazz singing competition and vocal practice workshops originally initiated in Poland by Grzegorz Karnas and which has spread to some fifteen countries is probably the most revealing phenomenon of this interest in jazz singing in Europe and Asia. So don’t be surprised if couleursjazz.fr dedicates an article to Voicingers soon.

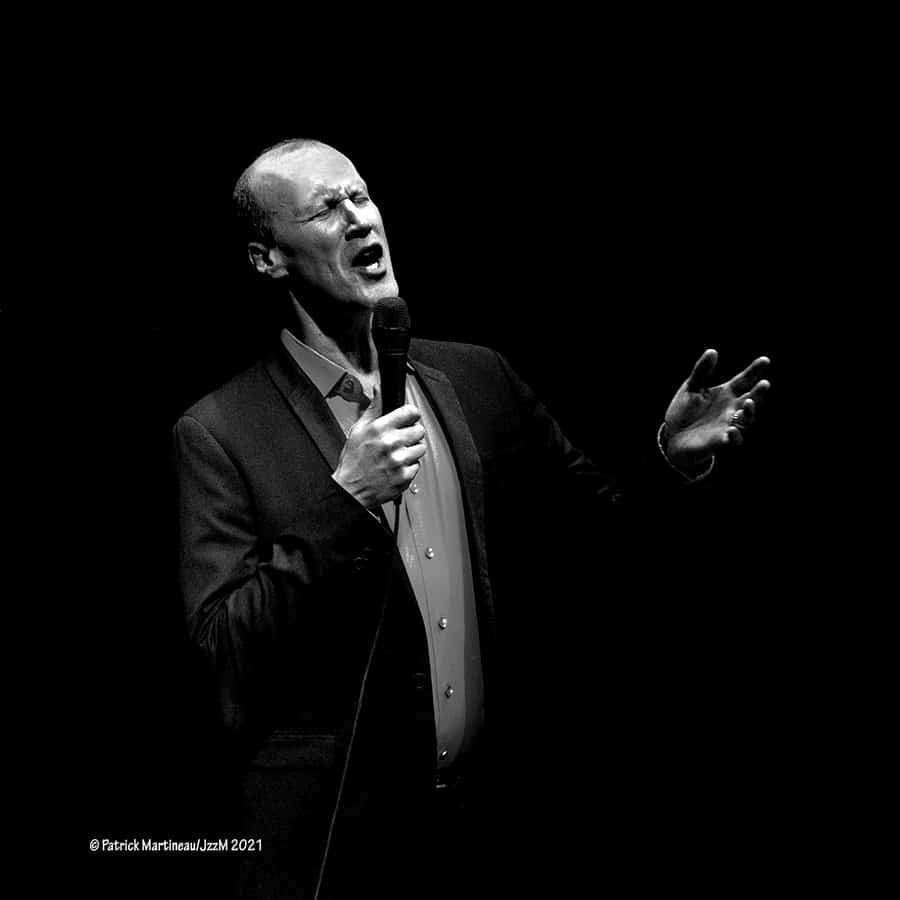

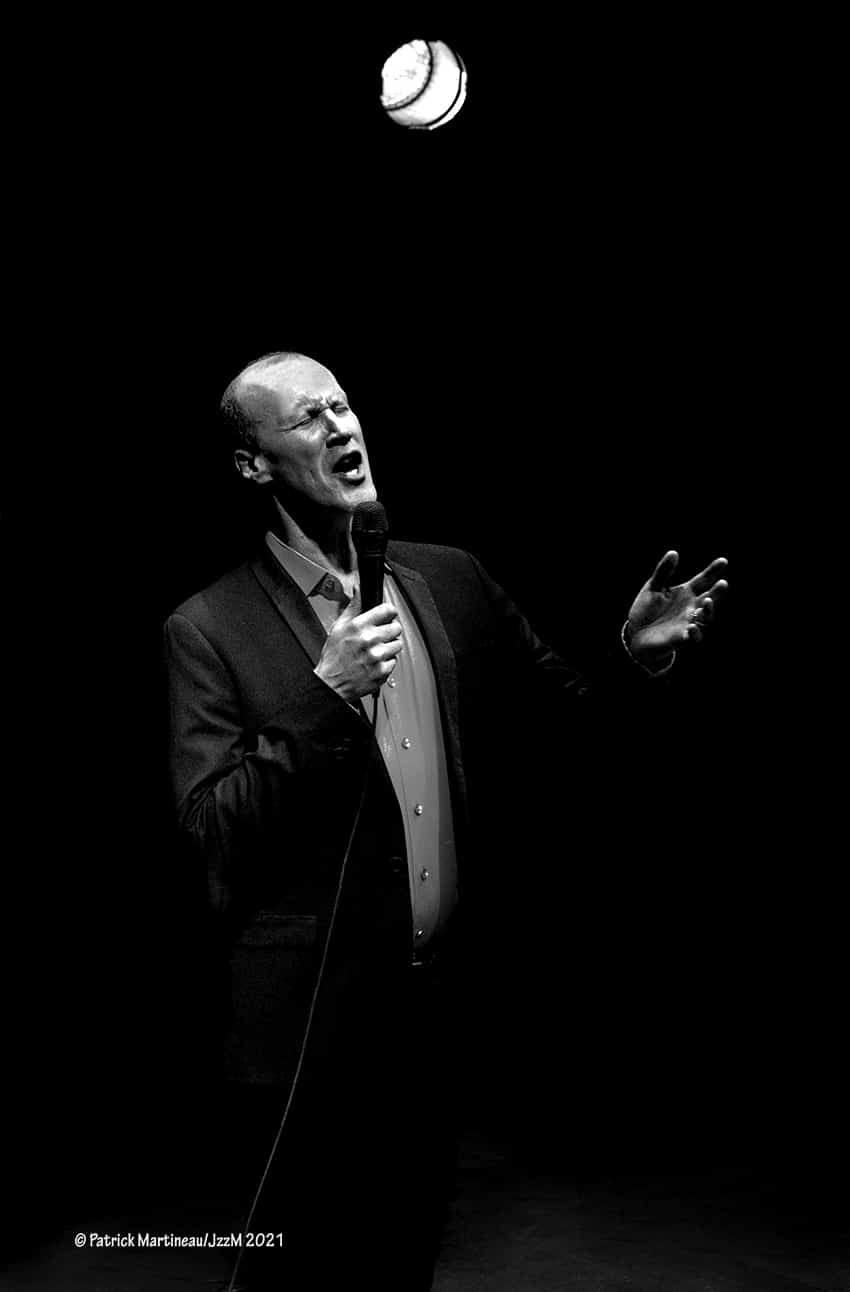

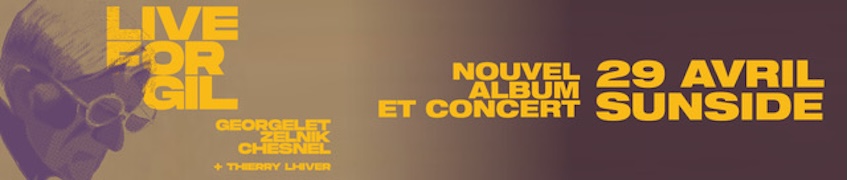

©Photos :

- Loïs Le Van: Bruno Belleudy

- Andreas Schaerer : Reto Andreoli

- David Linx : Patrick Martineau

- Kevin Norwood: Joana Luz

- Manu Domergue : Bruno Belleudy

- Ian Shaw : Joan Wolf

- Gzregorz Karnas : Bogdan Krezel

- Michael Schiefel : Stefanie Marcus

- Thierry Péala : Pedro Lombardi

- Gabor Winand : all rights reserved

RECENT COMMENTS